The gluten-free, casein-free diet is a popular intervention for those with autism spectrum disorder, particularly children. In honour of Autism Awareness Month, we explore the evidence for the GFCF diet in autism management and critically examine the “opioid excess” theory.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong developmental disability that affects how people communicate and interact with the world. Autism exists on a spectrum, meaning people can experience a wide range of symptoms of varying severity. The causes of autism are unclear, though it likely results from a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Table of contents

- What is the gluten-free, casein-free diet?

- Why restrict gluten and casein?

- Weighing up the evidence

- Is a gluten-free, casein-free diet safe?

- Final verdict

What is the gluten-free, casein-free diet?

A gluten-free, casein-free (GFCF) diet is a popular intervention for autistic children. As the name suggests, it is a diet that cuts out two proteins, namely gluten and casein.

According to a UK survey of parents with autistic children, 29% have trialled the diet. Of this group, 20-29% reported significant improvements in their child’s overall ASD behaviours, such as concentration and social communication.

Likewise, an online survey in 2006 found that 27% of parents with autistic children had tried the GFCF diet. Without a doubt, the GFCF diet is the most popular and best-studied dietary intervention for ASD.

☝FACT CHECK☝ A large and robust body of research shows that there is no link between autism and vaccines.

Why restrict gluten and casein?

There are several hypotheses for why excluding gluten or casein might improve autism. One of the most popular is the “opioid excess” theory, which surmises that peptides enter the bloodstream via the gut, affecting the central nervous system and penetrating the blood-brain barrier.

The hypothesis was first suggested in 1979, when Paksepp et al. observed apathy and social isolation in mice fed casomorphin, an opioid-like peptide from casein milk protein.

In short, casein and gluten are broken down into peptides with opioid-like activities in the gut. According to the “opioid excess” theory, autistic individuals suffer increased intestinal permeability in the gut lining, colloquially referred to as “leaky gut”.

In support of the theory, its proponents cite studies indicating an increased occurrence of “leaky gut” and higher urinary peptide levels in those with ASD.

To take one study, researchers measured the intestinal permeability of 90 ASD subjects and 146 of their first degree relatives. In support of the “leaky gut” theory, 36.7% of the ASD subjects had increased IP, compared to 21.2% of their relatives and 4.8% of healthy controls.

Likewise, a 1996 study published in the journal Acta Paediatrica found that 9 of 21 autistic subjects had altered intestinal permeability, whilst no one in a control group of 40 displayed abnormalities.

Whilst some studies report these biomarkers (high urinary peptide levels and compromised gut wall), neither is consistently observed in autistic individuals, diminishing the link between gluten, casein and autism.

Then again, others have proposed that the causes for ASD are plural, which would explain the variability in results.

GFCF advocates often reference the high prevalence of gastrointestinal issues in children with autism to support their case. For example, a review in 2006 found that 70% of autistic children had gastrointestinal problems compared to 42% of children without a diagnosis of autism.

Interestingly, the severity of GI symptoms appears to be correlated with the severity of autism symptoms, suggesting a link. What’s more, a modest co-morbidity has been suggested between coeliac disease and ASD.

A review study examining the opioid excess theory, published in 2021, concluded that the hypothesis has neither been proved nor discredited. In light of this, the paper calls for more high-quality research to test this proposed mechanism for autistic behaviours.

☝DID YOU KNOW?☝ Boys are four times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with ASD

Weighing up the evidence

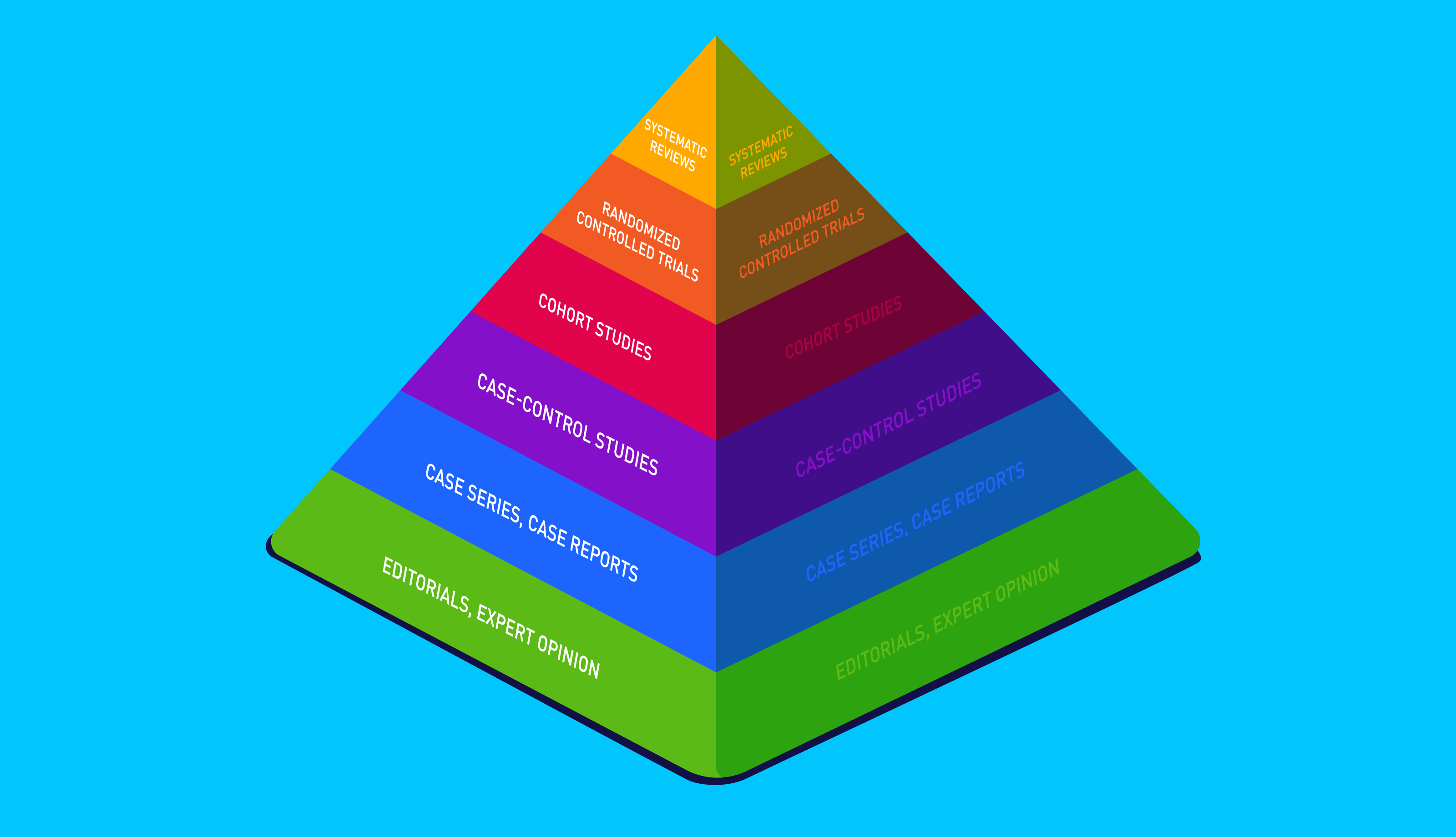

Whilst the GFCF diet enjoys anecdotal support, clinical studies have returned less conclusive evidence. Moreover, support for the GFCF diet largely relies on case studies and self-reported improvements instead of direct measurements, many of which lack double-blinding. Let’s take a closer look.

In a randomised, controlled, single-blind study, Knivsberg et al. compared a GFCF diet with a control group, measuring autism symptoms before, and after, a year. All participants were children with ASD and urinary peptide abnormalities, numbering twenty in total.

Knivsberg et al. reported that the GFCF group saw significant improvement in autism symptoms compared to the placebo group, including improved attention, communication, and social/emotional skills.

Despite promising results, the study was marred by design flaws; like most research on the GFCF diet, the parents knew if their child was in the placebo group.

Additionally, the primary data used to measure outcomes were subjective interviews with the parents, increasing the risk of bias and limiting the studies' reliability. With that said, the study is one of only a few to use a control group and is significantly longer than other trials examining a GFCF diet.

A 2006 overview of seven studies concluded that research on GFCF diets for autism were insufficient to recommend the intervention, owing to methodological flaws such as a lack of blinding.

The authors stressed the need for placebo-controlled, double-blind studies in light of these methodological flaws. In 2006, researchers conducted a preliminary double-blind, randomised trial testing the efficacy of GFCF in treating autism behaviours.

The study involved fifteen 2-16-year-olds with ASD and lasted 12 weeks in total. Additionally, the researchers made direct observations and measured urinary peptides levels. Despite the improvements in study design, the trial was uncontrolled.

Although several parents reported improvements, there were no statistically significant differences between the placebo and study groups on autism symptom severity.

With that said, the study sample was small, and the experiment was short-lasting, leaving the results open to criticism. More recently a double-blind challenge trial followed 14 autistic children aged 3-5 for six weeks whilst trialling a GFCF diet.

After this period, half the participants received casein and gluten products, though neither the parents, participants, nor researchers knew who received them. Once again, the GFCF diet had no statistically significant impact on the participant’s symptoms compared to a placebo.

The authors advise caution due to the small sample size of fifteen. Additionally, the paper calls for large-scale studies to determine whether the diet may help a small subset of autistic children improve their symptoms.

In response to these studies,some researchers have argued that dietary interventions take at least 3-6 months to take effect, labelling short-term interventions a “waste of time and money”.

In 2020, the journal Nutrients published a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Their search turned up six RCTs with a total of 143 participants.

Overall, the review found no effect of a GFCF diet on core autism symptoms; on the contrary, the diet was slightly associated with an increased risk of digestive upsets. More damningly, the quality of evidence was ranked as high risk for bias, inconsistency and imprecision. In line with previous studies, the paper calls for better quality RCTs.

☝STUDY TIP☝ Double-blind means neither the researchers or participants know who received the placebo.

Is a gluten-free, casein-free diet safe?

Continuing, autistic children are at particular risk for nutrient deficiencies as they often have “favourite” foods and restrictive dietary preferences. Examples of dietary rigidity include:

- Having a preference for specific textures (such as crunchy or soft foods)

- Favouring certain food brands

- Preferring food cut in a certain way (e.g. toast cut into squares but not triangles)

- Choosing predictable food. For example, a packet of crisps often has the same shapes, textures and colours, whereas a banana might vary in taste, colour and appearance.

If a GFCF diet restricts one of a child's already limited preferences, it could be particularly detrimental to their health. With this in mind, it is vital that parents who wish to try the diet consult a qualified dietician.

Moreover, gluten-free alternatives come at a price, literally. According to a 2018 study in the UK, gluten-free products cost 159% more than their glutinous counterparts! The same study showed that bread products are around 267% more expensive on average. If you’ll excuse the pun, that’s a lot of dough.

Lastly, some researchers have raised concerns that a GFCF diet could increase the risk of social isolation. For example, a GFCF diet stops children from eating the same food as their peers and may complicate eating out.

Final verdict

In conclusion, the research does not permit us to recommend a GFCF diet for the management of autism in those without coeliac disease or non-coeliac gluten sensitivity.

Whilst some studies show promise, these are marred by methodological flaws, including a reliance on subjective data and a lack of blinding. On the balance of evidence, the National Institute For Health And Care Excellence (NICE) advises against using the diet “...for the management of core features of autism in children and young people”.

Likewise, evidence for the opioid excess theory is limited and mixed. Whilst the theory has not been disproven, the evidence is insufficient, pending better quality research.

Given the popularity of the GFCF diet and the large body of anecdotal evidence in its favour, large-scale group studies should be undertaken with extended test periods. This will help researchers determine whether a small subset of autistic individuals could benefit from the diet.

Lastly, parents who wish to undertake the diet should weigh up the financial and social costs with the uncertain benefits. Most importantly, the GFCF diet should be supervised by a qualified dietician to minimise the risk of nutritional deficiencies.

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.