Our gut microbiome is intimately linked with the immune system. Discover how gut bacteria interface with immune cells, including how this may impact your risk of long-COVID and inflammatory disease.

- The immune system

- Immunity in the gut: Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT)

- Gut microbiota and immune cell education

- The hygiene hypothesis

- The microbiome and chronic inflammation

- What does a healthy microbiome look like?

- Diet and immunity: eating for immune health

- The microbiome, immunity and long-COVID

- Summary

You play host to millions of bacteria in your gut, collectively known as the microbiome. Weighing as much as the brain and outnumbering your human cells, this community of microbes is central to your immune health, even training immune cells to maintain immune homeostasis.

What’s more, depending on the diversity and balance of your gut bugs, the microbiome can either soothe the immune system or trigger an immune response.

The good news is that we can fight inflammation by making lifestyle and dietary changes, influencing immune health via the gut microbiome.

☝TIP☝By examining the balance and richness of your microbiome, the Atlas Microbiome Test can calculate your risk level for inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis.

The immune system

Our immune system is a complex network of organs, cells and tissue that coordinate with each other to fight off invaders and repair damage.

When your body initiates an immune response to trauma, this is known as acute inflammation and is a vital function that helps us heal and recover from injury.

A healthy immune system maintains a balance between tolerating benign substances and attacking unwelcome invaders, be that pathogenic bacteria or viruses. In the scientific literature, this state of equilibrium is called immune homeostasis.

So what happens when this careful balance is upset? If your immune system becomes overactive, it can lead to asthma, eczema, and allergies. In all of these conditions, the immune system overreacts to harmless antigens and initiates a disproportionate immune response.

Continuing, emerging research implicates the microbiome in the development of allergies and autoimmune disorders, as we will touch upon a bit later.

On the other hand, an underactive immune system can leave you susceptible to infection by foreign invaders.

For example, Severe Combined Immunodeficiency Disorder is a disorder where children are born without crucial white blood cells. The condition is often called “bubble boy disease” after David Vetter, a young boy who had to live within a protective bubble due to a compromised immune system.

Besides genetics, smoking, excessive drinking and poor nutrition can all compromise the immune system.

Medications, particularly chemotherapy, also weaken the immune system, making individuals vulnerable to attack from antigens.

☝TIP☝ Check out the daily Green Stack supplement from Hence. Packed full of antioxidants such as black pepper, turmeric and spirulina, this all-natural, plant-based powder can support a healthy immune system.

Immunity in the gut: Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT)

The lymphatic system is a major component of the human immune system. This complex network of lymph nodes, vessels and organs run throughout the body, transporting immune cells called lymphocytes.

There are two types of lymphocytes, namely B cells and T cells, which determine the immune response to antigens (foreign bodies).

T cells originate from bone marrow and mature in the thymus, both of which are lymph organs. Within the thymus, T cells multiply and become one of four types of immune cell, including:

- Helper T cells (“Let me at them!”)

- Cytotoxic T cells (“We need backup. Over.”)

- Memory T cells (“We don’t forgive, and we don’t forget”)

- Regulatory T cells (“Make peace, not war”)

Helper T cells produce cytokines whose job is to signal cytotoxic T cells. Both of these immune cells are pro-inflammatory.

In contrast, regulatory T cells are anti-inflammatory and soothe the immune response, minimising inflammation and the production of antigens.

Lastly, memory cells are T-cells that target antigens the body has encountered before. Unlike standard t-cells, they can rapidly and robustly initiate inflammation when they encounter an old foe.

B cells help to produce a type of protein called antibodies, which bind to foreign substances such as toxins and prevent them from docking healthy cells.

The human gut houses 70% of the body’s immune cells

Our gut houses 70% of the body’s lymphoid immune cells, located along the intestinal lining in Gut Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT).

Much of this tissue is concentrated in a small, dome-like structures along the intestinal mucosa called Peyer’s patches but can also be found in the appendix.

These immune tissues coordinate an inflammatory response to harmful pathogens and also promote tolerance to harmless microbes passing by.

Every day, immune cells in GALT are exposed to foreign substances that they must screen as they pass, like security at the airport checking each bag.

Small dendritic cells within GALT extend an “arm” through the gut barrier and sample passing particles. After assessing the antigens, they either activate an inflammatory response, activating T-helper cells or an anti-inflammatory response, activating T-reg cells.

When the system functions well, these cells maintain a delicate balance between tolerating harmless particles and eliminating harmful intruders.

So, how does our gut know which bacteria to accept and which ones to attack? As it turns out, our gut bacteria play an essential part in training our immune cells.

The gut and immune cell education

It may be surprising, but immunity is not hard-wired into our genes; from around one to five years old, our gut bacteria train GALT immune cells to tolerate beneficial and commensal bacteria, preventing unnecessary inflammation.

It is thought that the more diverse the microbiome, the better the immune cells will become at distinguishing between harmful pathogens and harmless bacteria.

In those with greater diversity, the immune cells will get a broader education which will serve them later on. And what happens in the gut doesn’t stay in the gut but impacts the entire immune system throughout the body.

In light of this, some speculate that disruption to the early microbiome could lead to health issues in adulthood, an idea researchers coined the hygiene hypthosesis.

The hygiene hypothesis

The foetus resides in the mother’s womb, sheathed by an amniotic sac during pregnancy. In this cocoon, the baby is sustained by blood and food purified via the mother’s immune system, not yet having one of its own.

Once the amniotic sac is pierced, the baby is baptised with millions of bacteria found in the vaginal canal. In the first three years of a baby's life, their microbiome will slowly be shaped before stabilising.

During these years, babies pick up microbes from breast milk and the environment; whenever an infant plays in soil or chews a toy, new species of bacteria enter their body and seek to set up shop; many perish on the journey to the colon, but a hardy few founding fathers will pioneer new communities.

Interestingly, our immune system is biased towards anti-inflammatory, immune cells whilst the microbiome is developing, increasing the chance of bacterial colonisation.

Evidence suggests that reduced diversity and balance during the microbiome development, generally from 1-3 years old, may increase the risk of allergies and autoimmune disease long-term.

For example, children born via c-section have been observed to have markedly different microbial compositions compared to those born via the vaginal canal. What’s more, they also appear to have increased rates of asthma and allergies.

In the Western world, we enjoy low rates of infectious diseases due to scientific developments and innovation. But parralel to this, the West has seen a dramatic rise in allergies and autoimmune disorders.

A growing group of microbiome researchers believe that an increase in c-section births, hyper-cleanliness and excessive antibiotic use may be to blame, all of which disrupt the developing microbiome and, by extension, immune education.

Whilst a c-section birth or bottle-feeding may have raised your risk of allergies, it is far more productive to focus on managing your immune health in the present.

Moroever, the microbiome is dynamic and responds to dietary and lifestyle changes. As such, you can support your immune health by cultivating diversity and balance in the gut microbiome.

The microbiome and chronic inflammation

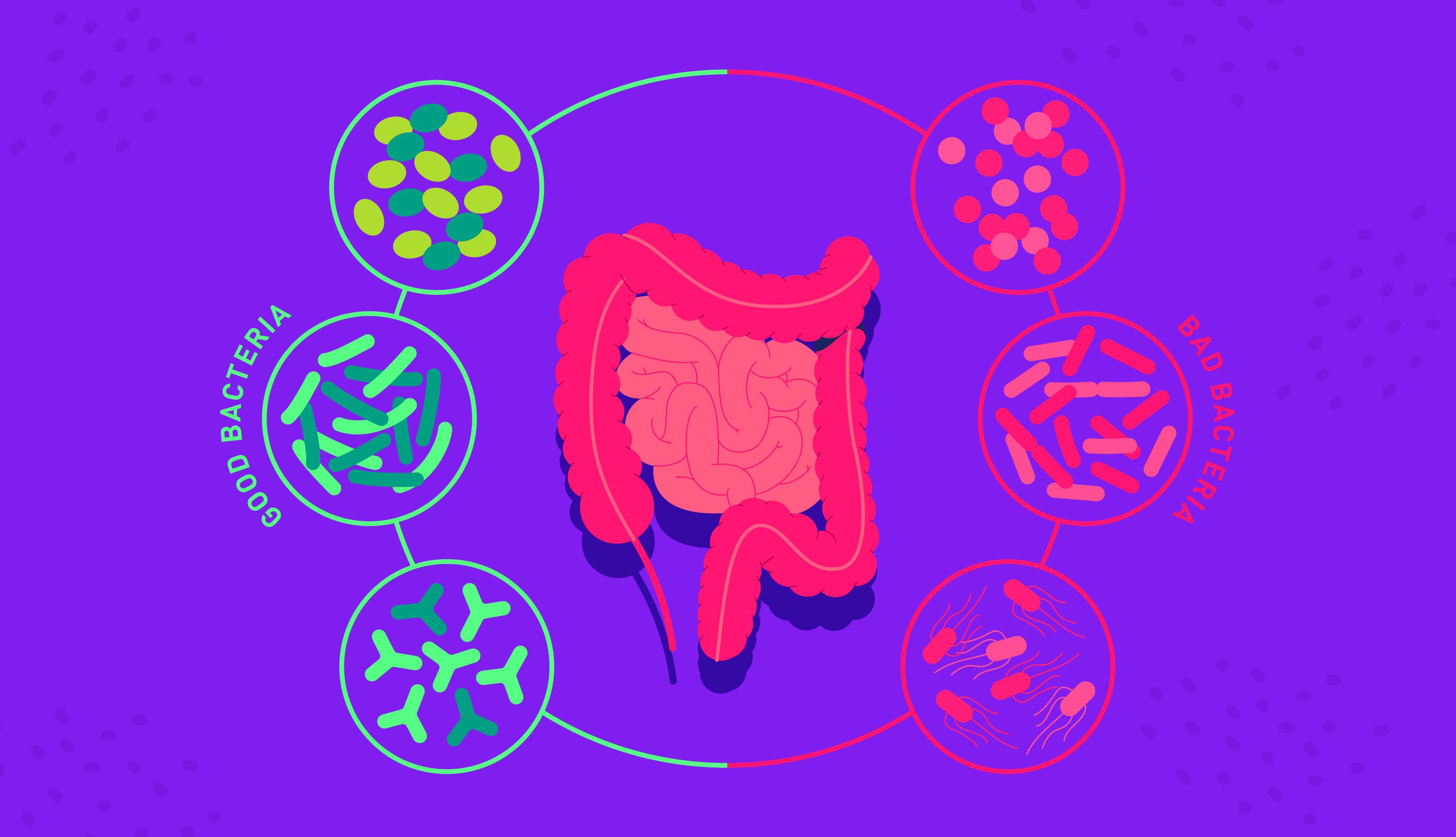

The interaction between our gut bacteria and the immune system doesn't stop after our early immune education. On the contrary, the balance and richness of our microbiome continue to influence levels of inflammation in the body.

Besides educating immune cells, our gut bacteria and their metabolites can soothe the immune system or trigger an inflammatory response, depending on their balance and richness.

Butyrate fuels the cells in the gut lining, thereby protecting against chronic inflammation. Moreover, it can also stimulate immune-soothing T-reg cells which mediate our bodies immune response.

Emerging research also suggests that microbiome composition can influence the production of interleukin-10, a powerful anti-inflammatory cytokine.

On the other side of the coin, some bacteria produce pro-inflammatory substances, activating cytokines and hot-headed T-helper cells.

Gram-negative bacteria contain lipopolysaccharides in their outer wall, an endotoxin that promotes an inflammatory response.

When gram-negative bacteria die, these endotoxins are released into the surrounding environment.

If these compounds cross the gut lining and enter the bloodstream, they can lead to chronic and systemic inflammation.

In a healthy gut, the epilithic lining (gut wall) will prevent most endotoxins from activating GALT immune cells, however, poor microbiome diversity can lead to problems.

More specifically, an imbalance in the microbiome is associated with increased intestinal permeability, more commonly known as "leaky gut". When this happens, more LPS can enter the promised land of the body, setting off inflammatory alarm bells from immune receptors.

☝TIP☝ With the Atlas Microbiome Test, you can discover the inflammatory potential of your gut microbiome. We’ll also send you personalised, weekly dietary tips to encourage diversity and support immune health.

What does a healthy microbiome look like?

Luckily, the microbiome is dynamic and plastic, meaning we can mould its composition through our diet and lifestyle choices. So how does a healthy microbiome look?

Your microbiome is what you eat

Whilst the specific species may differ across individuals, researchers unanimously agree that diversity and balance are vital markers of microbiome health.

On the contrary, low diversity and imbalance are associated with numerous inflammatory diseases, including Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis.

Think of it as a forest in which lots of different species of bacteria work together to keep the system stable; if there are too many of one species or not enough of others, the forest can suffer.

Diversity is beneficial because it makes the ecosystem more robust; a forest with numerous species has a better chance of bouncing back if its disrupted by fire, for example.

Likewise, balance is important to the health of the forest as it prevents a takeover by one species; It’s okay if there are a few weeds among the trees, but too many would threaten the ecosystem’s careful balance.

Your microbiome is no different, although you control the weather and shape the ecosystem within your inner jungle.

Diet, microbiome and immunity: eating for immune health

Numerous factors can disrupt the makeup of your gut flora and deplete diversity, including:

- excessive antibiotics

- stress

- poor diet (lack of fibre in particular)

- sedentary lifestyle

Returning to the forest analogy, a diet rich in plant-based fibre, whole grains, fruit and legumes is like compost for beneficial bacteria.

All these foods contain resistant starch, an indigestible fibre that your enzymes struggle to break down. Because of this, they pass undigested to your colon, where probiotic bacteria feast on them.

As we touched upon earlier, butyrate fuels the cells in your gut lining, reinforcing the barrier between your gut and bloodstream.

By doing so, butyrate can reduce your risk of chronic inflammation and reduce intestinal permeability, colloquially known as “leaky gut”. Additionally, butyrate can stimulate soothing T-reg cells in GALT tissue, helping to combat unnecessary inflammation.

In a study at the University of Gronigen, a team of gastroenterologists analysed the microbiome of 1425 people, split into the four cohorts: those with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome and the general population.

The results showed that dietary patterns comprising legumes, breads, fish and nuts were associated with a lower abundance of opportunistic bacteria, fewer endotoxins and less inflammatory markers in stool.

On the contrary, a higher intake of animal foods, processed foods, alcohol and sugar corresponded with a microbiome biased towards inflammation.

As we have discussed, chronic inflammation is associated with numerous health conditions. Among them are:

- depression

- heart disease

- cancer

- arthirtis

- inflammatory bowell diseases (ulcerative colitis & Crohn's)

Numerous studies have shown that following the diet is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease, stroke, obesity and type-2 diabetes.

| Barley | Oats | Rye |

| Bran | Whole grains | Mushrooms |

| Apples | Citrus | Berries | Onions | Garlic |

Prebiotics that promote butyrate production

☝TIP☝ Take an Atlas Microbiome Test and discover how well your gut flora synthesises butyrate. Based on your results, we will generate weekly, personalised nutritional advice to encourage butyrate production and support your immune health.

The microbiome, immunity and long-COVID

Post-COVID syndrome, colloquially known as “long-COVID”, is characterised by persistent symptoms for weeks or months after infection. Fatigue, weakness and insomnia are the most commonly reported symptoms.

Researchers aren't sure what causes some people to experience long covid, though they suspect that exaggerated immune response or cell damage likely play a part.

Considering that the microbiome is closely linked with immunity, researchers sought to discover whether the microbiome might play a part in who develops long-COVID.

To this end, a team of scientists measured the microbiome diversity of 106 individuals with varying degrees of COVID-19 and a control group of 68 individuals without COVID. The results were published in the prestigious peer-reviewed British Medical Journal.

Patients who developed long-covid were found to have had a less diverse and abundant microbiome.

Parallel to this, the gut microbiome of patients who didn’t develop long COVID was similar to those who hadn’t had COVID-19.

After analysing the microbiome of those with long-covid, researchers discovered that their gut bugs were depleted of bacteria known to boost immunity, including:

- bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum

- f. prausnitzii

- roseburia hominis

Summary

The gut microbiome is intimately linked with the immune system; not only do gut bacteria play a key role in educating immune cells, but bacteria and their metabolites can both stimulate and soothe our immune response.

Moreover, a microbiome lacking diversity and predominated by pathogenic bacteria can increase our risk of inflammatory diseases. On the contrary, a microbiome characterised by balance and enriched in probiotic bacteria can protect against chronic inflammation and disease risk.

Unlike our genes, the microbiome is dynamic and responsive to our diet and lifestyle. With this in mind, we can support our immune health by eating a diet rich in prebiotic plant-based fibre and low in fats. By doing so, we encourage the production of anti-inflammatory metabolites such as butyrate.

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.