Your mouth is home to over 700 different microbes, making up the oral microbiota. However, they could be affecting your gut and your wider health.

The microbes in your mouth are an important part of a natural ecosystem in the oral cavity. It’s not possible to see them, but they are there. And yes, they’re there when you eat, drink, sleep, and passionately kiss your significant other. So, numbers may not be the only thing you swap on a first date!

The microbes in your mouth include bacteria, viruses, and fungi, but bacteria make up the majority. Living in the mouth means that they have access to your gut via the digestive tract, and can even access your bloodstream.

Table of contents

- What is the oral microbiota?

- How do oral bacteria get into the stomach biome?

- The link between gut and oral dysbiosis

- Oral microbiota and the gut barrier

- Oral microbiota and disease

- What’s the best oral dysbiosis treatment?

Unlike the microbial ecosystem in the gut, the composition of oral bacteria is similar in healthy people across different countries. However, just like gut microbes, oral bacteria are associated with a variety of diseases both orally and throughout the rest of the body.

What is the oral microbiota?

Your mouth is home to hundreds of different microorganisms, be it bacteria, viruses, or fungi, that make up an important ecosystem in your mouth.

The oral microbiota is a complex microbial ecosystem which helps to maintain a stable mouth environment. Within the mouth, there are also microenvironments, like on the teeth, tongue, hard and soft palates, where bacteria also colonise.

Body parts that have microbiomes:

- Mouth

- Gut

- Skin

- Vagina

- Lungs

- Eyes

The mouth is a complex environment because it’s made up of many structures which are appealing homes for bacteria. The environment within the mouth is also perfect for microbes because it is relatively warm and is a source of nutrients and water.

The most prevalent bacteria in the oral cavity are members of the Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinomycetes phyla. However, contrary to the colon, the bacterial ecosystem is relatively stable and is not prone to significant changes.

The oral microbiome is one of the most abundant in the human body, second only to the gut. The different members of the oral microbiota coexist in dense communities known as biofilms. However, some research suggests that biofilm bacteria are part of a group known to cause chronic disease.

The gut microbiome

The gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem consisting mainly of bacterial cells, but also viruses, archaea, and fungi which work in harmony with the human body. It provides a range of benefits like strengthening the gut barrier, supporting the immune system, providing energy, and protecting you from opportunistic pathogens which could make you ill.

When the conditions in your gut are at their best, the bacteria living in your gut live in symbiosis with you. Some are commensal – they are harmless – and others are beneficial because they carry out important functions like producing helpful metabolites, keeping your immune system strong, and stopping pathogenic microbes from wreaking havoc.

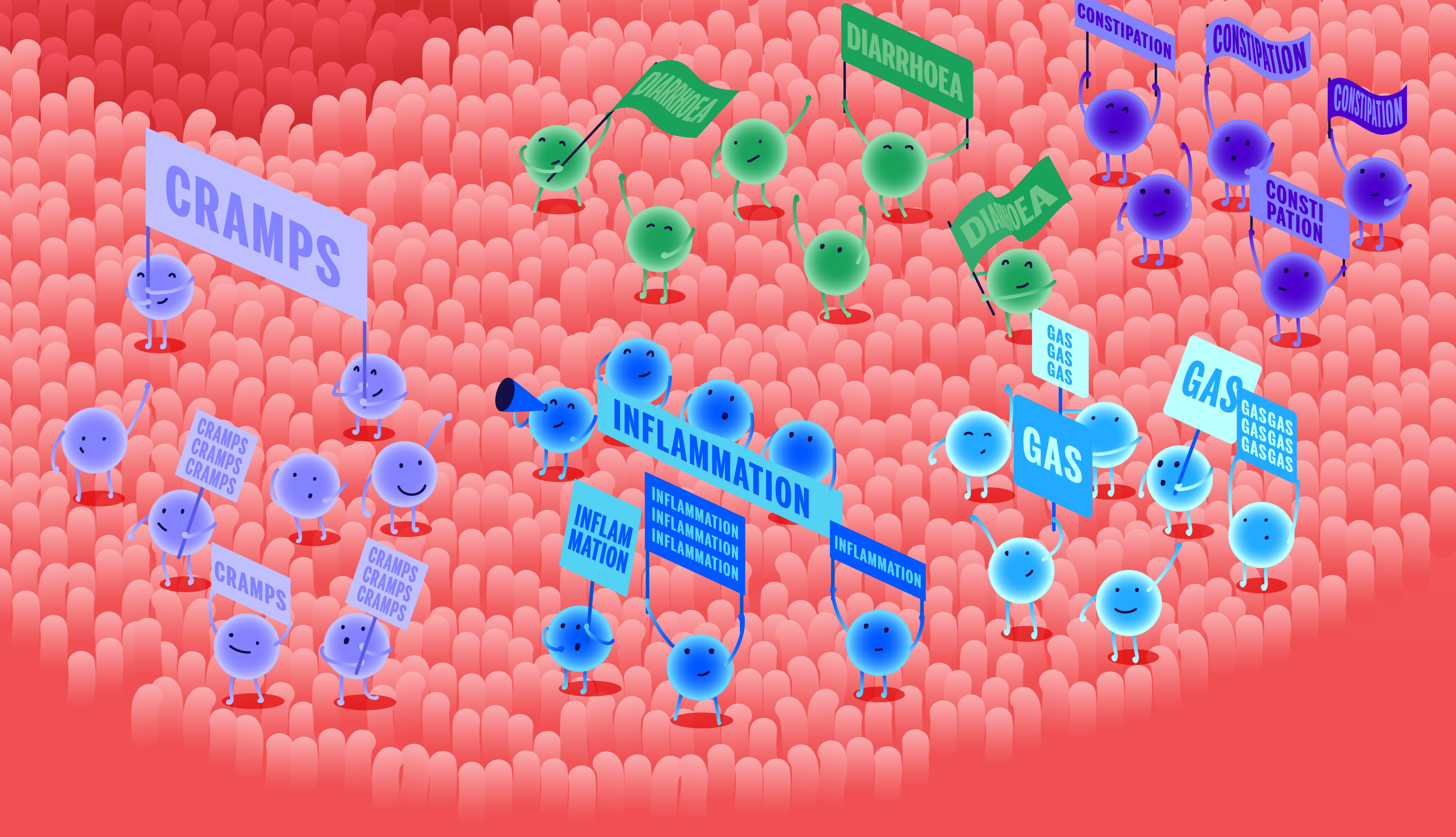

Yet, if dysbiosis occurs, pathogenic bacteria may dominate your gut or you may lack diversity of bacterial species, which is an important gut health parameter. Ultimately, this means your gut isn’t working in harmony with you. These microbes can release unhealthy metabolites and toxins, or trigger inflammation - all of which can affect your health and the happy bacteria in your gut.

☝TIP☝Find out how healthy your microbiome is with the Atlas Microbiome Test and get personalised diet recommendations.

How do oral bacteria travel to the stomach biome and gut?

Saliva is a major transporter of oral bacteria. Made up of 98% water, the human salivary glands can produce anywhere up to 1.5 litres every day. This essential liquid keeps the mouth hydrated and helps digest food.

What is saliva for?

- maintaining oral hygiene

- lubricating and binding food for swallowing ease

- flushing away food debris

- preventing bacterial overgrowth

- starting the process of starch digestion

Oral bacteria can hitch a ride in your saliva and spread throughout the body, including to the gut. Some are destroyed by stomach acid, others are acid-resistant, like Porphyromonas gingivalis which is also linked with an imbalance in the gut microbiome, also known as dysbiosis.

Generally, when you swallow, there will be lots of bacteria, but most won’t colonise the gut. However, in some serious diseases, increased amounts of oral bacteria have been reported in the gut, suggesting there is a link between the two.

In particular, medication for chronic gastric reflux, called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), may also facilitate the passage of microbes from your mouth to your gut because they reduce the production of stomach acid – an important microbial barrier.

☝FACT☝Studies show that oral bacteria can colonise the gut, activating inflammation.

Oral dysbiosis, gum disease, and the gut microbiome

There is strong evidence emerging suggesting that there is a link between the oral microbiome and the health of the gut.

Some oral bacteria, like P. gingivalis, are associated with gut dysbiosis. In the mouth, these bacterial cells cause periodontitis, a posh way of saying gum disease, but they’re also linked to a number of serious diseases that are associated with imbalances in the gut microbiome (dysbiosis).

If you have mouth issues like caries or gum diseases, swallowing bacteria associated with these problems can result in dysbiosis, where the gut microbiome becomes imbalanced and negatively affects health. Characteristically, there is either a high abundance of one microbe and not enough of others, or a lack of diversity in the microbiome.

Diseases associated with gum disease and gut dysbiosis

People who have gum disease may swallow a lot of P. gingivalis every day. This bacteria is particularly resilient to adverse conditions because it can withstand stomach acidity and travel to the gut. Here, it can trigger the immune system and promote inflammation, both of which can alter the composition of the gut microbiome, resulting in dysbiosis.

| obesity | type II diabetes |

| atherosclerosis | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| rheumatoid arthritis | gastrointestinal cancer |

| colorectal cancer | Alzheimer’s disease |

| pancreatic cancer | gastric cancer |

Oral microbiota and the gut barrier

An imbalance in the oral microbiota is to blame for gum disease which is associated with an increased risk of various other diseases.

The gut lining is a barrier, and a useful one at that. It works by allowing beneficial things like essential nutrients to leave the gut, enter the blood, and travel to places where they're needed. At the same time, the gut barrier stops pathogens, toxins, and food from entering the body and potentially making you ill.

The process is called intestinal permeability and it works through important mechanisms called tight-junction proteins. These act like gates and fences, when healthy they relax, or open, enabling nutrients to pass through them, but in unhealthy states, the gates or tight junctions may not close, allowing unwanted toxins to pass through easily.

One study shows that a single administration of P. gingivalis significantly changes the composition of the gut microbiome, and affects the function and integrity of the gut barrier.

What does this mean for your gut? Well, through impaired intestinal barrier function, endotoxemia occurs, that’s where substances called lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from bacteria enter the blood, resulting in inflammation and an immune response, therefore, increasing the risk of disease.

Oral microbiota and disease

Oral bacteria produce metabolites that influence the development of mouth diseases, but growing research is uncovering their role in other systemic diseases too.

The bacteria in your mouth can also affect you directly, without going through the gut. This happens when they get into your bloodstream through blood vessels in the mouth, leading to low-grade inflammation throughout the body and several diseases.

Obesity

Obesity is associated with increased gut permeability, so the gut barrier isn’t working as it should. Remember, some oral bacteria reduce the integrity of the gut lining and stop the tight junctions working effectively. It also increases the level of inflammation in the body which is known to trigger an increase in body weight.

In gum disease, pathogenic bacteria accumulate in the pockets of your gums. These pockets can become ulcerated, allowing pathogens and bacterial toxins to pass into the bloodstream. So, the oral microbiota alongside gut microbes could have a role in the onset of systemic inflammation and the subsequent development of obesity.

Diabetes

Type II diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases, particularly in the Western world. One of its main characteristics is persistently high blood sugar levels. There is evidence to suggest that oral diseases are linked with diabetes type II. Equally, oral symptoms are a complication of this metabolic disease, such as tooth loss.

The oral microbiota is an important factor in the development of diabetes in that it affects the development of bones in the mouth. There are also studies which show that there are distinct differences in the diversity of oral microbiomes between healthy people and people with type II diabetes.

Colon cancer

The gut microbiota is associated with an increased risk of colon cancer, so too is mouth bacteria. Some bacterial species like Fusobacterium nucleatum, a prevalent oral inhabitant, are also a risk factor for developing colon cancer.

Unlike other mouth bacteria that hitch a ride through the GI tract and meander their way through the stomach biome, F. nucleatum travel through the circulatory system and stick to the tumour cells in the colon.

It’s important to note that this bacterium isn’t usually present at all in a healthy gut, they prefer your mouth instead. A high level in the mouth, however, is linked with gum disease and tooth cavities.

The role of oral dysbiosis and other diseases

Oral dysbiosis is associated with other chronic diseases too, including rheumatoid arthritis. The mechanisms by which this disease and periodontitis are linked are similar in that the pathogenic bacteria cause inflammation and bone loss.

Other studies have shown that imbalances in the gut and oral microbiotas are closely related to the development of liver disease. When comparing the composition of the gut microbiomes of healthy people and those with liver cirrhosis, the latter was found to have high levels of oral bacteria in their gut.

What’s the best oral dysbiosis treatment?

Keeping your mouth in mint condition is a great way to keep pathogenic bacteria at bay and it really is quite simple.

A major cause of oral dysbiosis is poor mouth hygiene, but there are several other important factors that also come into play:

- Poor oral hygiene

- Dietary habits

- Smoking

- Gum inflammation

- Genetics

- Salivary gland dysfunction

For lots of people, brushing their teeth at least twice per day, regularly flossing (and, no not the dance craze), and rinsing with mouthwash can be a chore, but when it comes to dental hygiene, it shouldn’t be underestimated.

You can also focus on your lifestyle, like giving up smoking and eating wholesome foods that are not high in refined sugars. Improving your diet will also benefit your gut microbiome, because good bacteria are picky eaters and much prefer plant-based foods.

Food for a healthy mouth and gut microbiome

| yoghurt | apples | garlic |

| milk kefir | barley | onions |

| sauerkraut | berries | oats |

| kimchi | citrus | mushrooms |

☝FACT☝Can mouth bacteria cause stomach problems? The simple answer is yes, oral bacteria can spread through the body and are linked with several systemic diseases.

Oral dysbiosis and gut microbiome health: the bottom line

Who knew that the microbial residents in your mouth could upset the balance in your gut microbiome? Some oral bacteria species are cunning and can resist the harsh conditions of your stomach to reach the gut while others enter the bloodstream and hitch hike to the colon.

It’s clever stuff, but ultimately, a high abundance of oral bacteria in your gut can have negative consequences for your health, leaving you at a greater risk of certain diseases. Luckily, adopting good oral hygiene can be positive both for your dental health, but also your wider health.

Plus, eating a diet rich in whole plant foods (and thus, dietary fibres and nutrients) will help to keep your health-promoting gut bacteria thriving. Doing so will increase the activity of the bacteria, strengthen your gut barrier, and support the immune system.

- Abed, J et al. Fap2 Mediates Fusobacterium nucleatum Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Enrichment by Binding to Tumor-Expressed Gal-GalNAc, 2016

- Allaker, R, P and Stephen, A, S. Use of Probiotics and Oral Health, 2017* Bruno, G et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Dysbiosis: Current Knowledge and Aspects to be Clarified, 2014

- Chelakkot, C et al. Mechanisms Regulating Intestinal Barrier Integrity and Its Pathological Implications, 2018

- Flynn, K, J et al. Metabolic and Community Synergy of Oral Bacteria in Colorectal Cancer, 2016

- Kato, T et al. Oral Administration of Porphyromonas gingivalis Alters the Gut Microbiome and Serum Metabolome, 2018

- Lu, M et al. Oral Microbiota: A New View of Body Health, 2019

- Nakajima, M et al. Oral Administration of P. gingivalis Induces Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota and Impaired Barrier Function Leading to Dissemination of Enterobacteria to the Liver, 2015

- Neves, A, L et al. Metabolic Endotoxemia: A Molecular Link Between Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk, 2013

- Olsen, I and Yamazaki, K. Can Oral Bacteria Affect the Microbiome of the Gut, 2019

- Shang, F, M and Liu, H, L. Fusobacterium nucleatum and Colorectal Cancer: A Review, 2018

- Tam, J et al. Obesity Alters Composition and Diversity of the Oral Microbiota in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Independently of Glycemic Control, 2018

- The Marshall Protocol Knowledge Base. Microbes in the Human Body, 2020

- Thursby, E and Juge, N. Introduction to the Human Gut Microbiota, 2017

- Tiwari, M. Science Behind Human Saliva, 2011