Eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis, affects up to 20% of children and 3% of adults around the world. This inflammatory condition is characterised by skin rashes and severe itching.

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic and challenging condition that can significantly lower a person’s quality of life, taking a toll on mental health too. There is no cure, but there are treatments that can alleviate the symptoms of eczema.

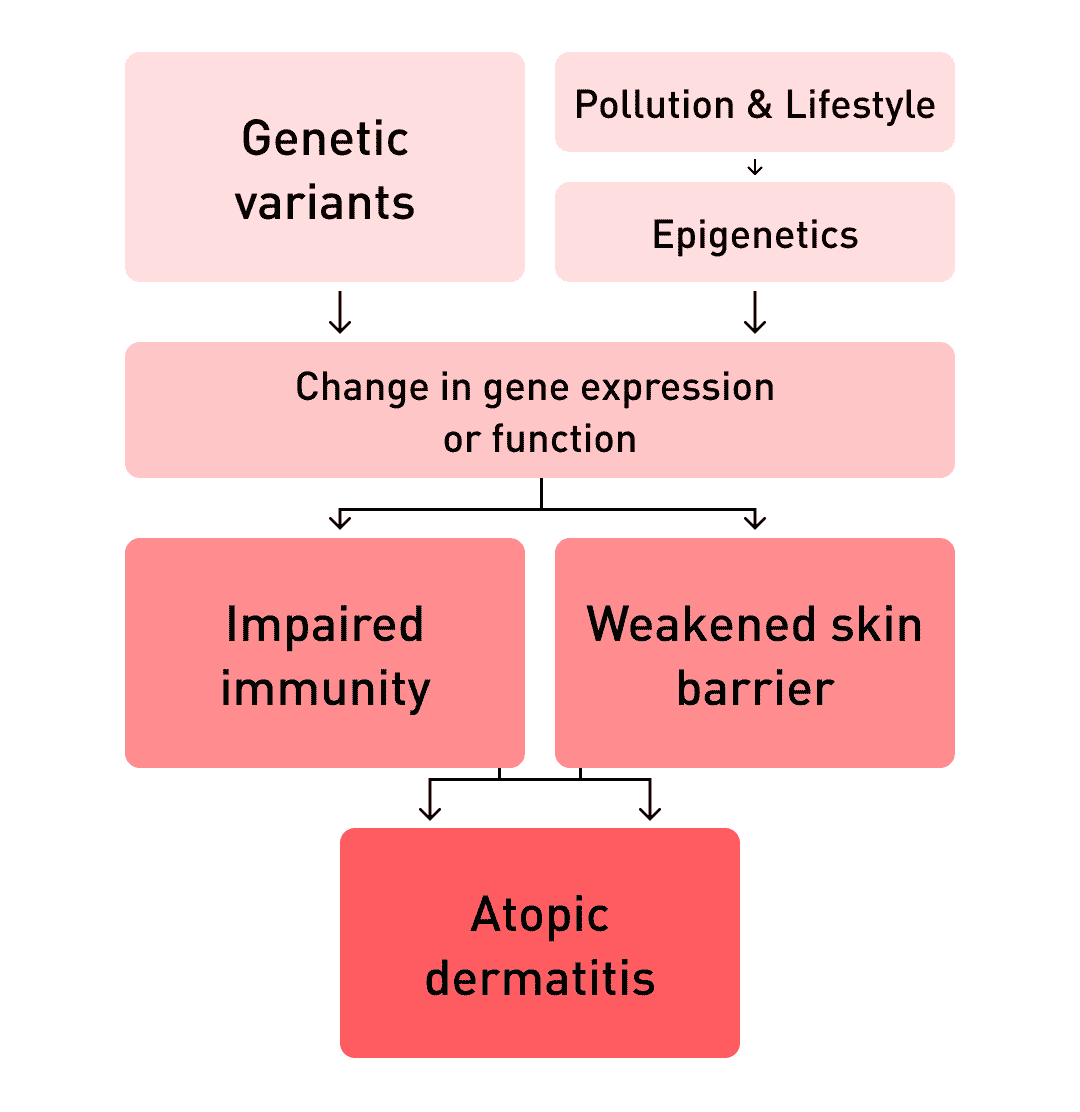

This condition is caused by a combination of factors, primarily a person’s genetics and environment. New research has also shown how imbalances in a person’s skin microbes, and even the gut microbiome may participate in the development of atopic dermatitis.

This article will explore the causes and symptoms of atopic dermatitis, how genetics, environment and microbes contribute to it, and recommendations to manage this chronic condition.

Table of contents

- What is atopic dermatitis?

- Eczema triggers in the environment

- Heredity: the genetics of atopic dermatitis

- Skin microbiome and atopic eczema

- The gut-skin axis

- Diet and food allergies

- The hygiene hypothesis

- Vitamin D and sunlight

- How to reduce your risk

What is atopic dermatitis?

Atopic dermatitis is characterised by rashes that typically affect the creases of the elbows and knees in adults. In children, eczema also affects the neck folds and cheeks. However, many children affected by atopic eczema grow out of it in adolescence.

In atopic dermatitis, the inflamed skin becomes itchy and flaky. When scratched, the rash may weep and crust over. Rashes that affect the joints, the back of the neck and behind the ears may become dry and cracked.

☝FACT☝Prolonged inflammation due to eczema can result in darkening or lightening and thickening of the skin.

Eczema triggers

Eczema is a condition that is difficult to treat because it is often hard to understand. One way to reduce the risk of an eczema flare-up is to identify triggers in the patient’s environment that can lead to an outbreak. Common eczema triggers include:

- Cold weather

- Certain foods

- Wool and synthetic clothing

- Detergents and household cleaning products

- Allergens

- Stress

- Heat and sweating

- Swimming pools

Heredity: the genetics of atopic dermatitis

Human genetics play a role in the risk of getting eczema. People with a family history of allergies and those with coeliac disease are more susceptible to this inflammatory condition.

Furthermore, people suffering from atopic dermatitis are more likely to suffer from food allergies, hayfever, and asthma. Eczema patients are also at higher risk of other inflammatory diseases, including Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hair loss (alopecia areata).

According to Medline Plus, a medical information website, “up to 60% of people with atopic dermatitis develop asthma or hay fever (allergic rhinitis) later in life, and up to 30 percent have food allergies.”

Skin barrier function

The skin is a critical part of the human body. It’s not just a physical barrier to the external world, it’s a chemical one too–the skin secretes oils, acids and other molecules that form a protective barrier.

When this skin barrier is healthy, it shelters bacteria that also help protect the body from external aggressions, like infections. However, it has been shown that patients with atopic dermatitis have a dysfunctional skin barrier, which lowers their protection from external factors such as:

| microbes | allergens |

| toxins | pollutants |

Researchers found that changes in the FLG gene, which encodes profilaggrin (a precursor to filaggrin), may partly be to blame. Filaggrin is an important protein that structures the epidermis, the outermost layer of skin. They suggest that mutations in this gene may make the skin more permeable and thus more reactive.

There are several other genes of interest too. Studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and half a dozen genes that encode proteins involved with skin barrier function.

Immune function

Researchers are also very interested in the role of genes that regulate the adaptive and innate immune systems. Studies show that genes involved in the activity of immune cells may result in abnormal immune activity in eczema patients when they are exposed to specific triggers, such as scratching, bacteria, and allergens.

DNA testing for atopic dermatitis

The Atlas DNA Test uses cutting-edge genetic sequencing technologies to identify genetic variants associated with the risk of developing atopic dermatitis. The calculation also takes into account environmental and lifestyle factors as well as family history.

Here are the risk factors computed by the Atlas health algorithm when calculating your personalised risk profile for eczema:

- Genetic variants that increase the risk of developing atopic dermatitis

- Diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma and other allergies

- Family history of atopic dermatitis and allergic diseases

- Lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity

More and more people are affected by atopic dermatitis: the incidence of this skin condition has doubled and even tripled since the 1970s in industrialised countries. Scientists believe that changes in our modern environment may be to blame.

The skin biome in atopic eczema

The skin of people diagnosed with atopic dermatitis differs from those without it. They have lower microbial diversity, fewer Streptococcus bacteria, and more Staphylococcus aureus, an opportunistic microbe that causes infections.

Interestingly, the skin microbiome of atopic eczema patients varies depending on whether they have skin lesions when swabbed. People with active skin inflammation have significantly disturbed microbial skin communities, especially an overgrowth of S. aureus where the rashes occur.

However, even in the absence of a flare-up, patients with eczema still have disturbed skin microbiomes with more S. aureus than healthy people. Just like in the gut, these findings highlight the importance of microbial diversity in human health.

The gut-skin axis

The gut microbiome is the body’s largest ecosystem of microorganisms. It is home to trillions of bacterial cells and some fungi, viruses, and archaea, which perform many important functions that help keep your whole body healthy.

70% of the immune system is located in the gut, where it has been trained by constant interaction with microorganisms since birth. The gut’s immune system is also at the heart of the gut-skin axis, which has an indirect impact on skin health according to recent research.

That’s because the gut and the skin can communicate via the immune system and the bloodstream. For example, gut bacteria produce molecules that can interact with the immune interface via the gut lining and bloodstream.

In autoimmune diseases and atopic dermatitis, the immune system doesn’t work properly and produces antibodies to harmless substances (like gluten) or even to the body’s own cells. This results in inflammation, which most commonly affects the mucous membranes, skin and intestines.

Diet and eczema

Take the Western diet, for example. This eating pattern, common in industrialised nations, is rich in fats, sugars, and meat. It is associated with increased risk of skin inflammation, as well as obesity, which is a risk factor for atopic dermatitis.

The Western diet causes imbalances in the gut microbiome, resulting in problems such as inflammation and an overabundance of pro-inflammatory bacteria; all of which can take a toll on the health-promoting attributes of our digestive microbes.

Gluten is another great example of the gut-skin axis. It has long been noted that people with gluten and coeliac disease are susceptible to a number of skin conditions.

- Coeliac disease is a food intolerance triggered by an immune reaction to gluten particles in the intestines.

- Gluten sensitivity is associated with specific gut bacteria that make particles that cause an immune reaction.

Hygiene and atopic dermatitis

Atopic eczema, like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, have all been linked to the “hygiene hypothesis”. This theory suggests that overly sanitised environments impair the development of the immune system in early childhood by limiting interaction with microbes.

These microbes are vital because they help train the immune system. If the environment is too sterile in childhood, it can leave adults more susceptible to autoimmune and allergic diseases later on.

- Family size: it is believed that if there are several children in a family, their microbiomes will develop more actively.

- Environment: big cities and polluted air reduce microbiota diversity, especially for children.

Sunlight and vitamin D

The skin can also have an impact on the gut. Sunlight triggers the production of vitamin D by skin cells, which are the body’s primary source of this nutrient. Vitamin D deficiency has been pinpointed as a risk factor for atopic dermatitis.

Humans get 80% of the body’s vitamin D needs from sunlight

Interestingly, one clinical trial showed that controlled and healthy exposure to UVB rays increased the diversity of bacteria in the gut. There is also evidence to suggest that some probiotics can help prevent atopic dermatitis, which adds yet another puzzling, but positive clue to the gut-skin axis mystery.

How to reduce your risk of atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a tricky and chronic condition, which can be helped by reducing your exposure to triggers that cause flare-ups. In addition to the traditional topical creams, some simple lifestyle measures can help:

- Keep a food diary to track what you eat and skin reactions. Work with a dietitian or nutritionist to identify potential triggers with an elimination diet.

- Get 5–30 minutes of sun exposure to your face, arms, hands, and legs (without sunscreen) daily (or at least twice a week), between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. except for summer or people with a family history of skin cancer.

- Avoid harsh chemicals (household cleaners, skin care products, chlorinated pool, etc.).

- Boost your gut microbiome with a healthy diet and cut down on sugars, fats, and meat.

- Give up cigarettes and stay away from passive smoke.