We swabbed 24 monuments in 13 cities of 9 European countries to see what bacteria live in on them. Here’s what we found.

Cultural enrichment is part and parcel of the holiday package when you head to a European capital, but have you ever wondered what bacteria are living on those monuments that everybody seems to touch or rub for good luck?

And, as humans, we are naturally inclined to physically interact with our environment, be it sliding our hands along the smooth surfaces of centuries-old monuments, scrolling through a social media feed on a phone, or surreptitiously touching our faces thousands of times every day.

At Atlas Biomed, we spend most of our working hours investigating the microbes in the human gut. But this summer, we decided to take a detour and see how human interaction with Europe’s iconic statues has influenced the microscopic ecosystems living there. In turn, we decided to spend some time considering how they might also interact with us.

Art in Amsterdam's Red Light district is avant-garde and at street level

These biomes (ecosystems of bacteria, yeasts and archaea) have unique signatures that reflect the volume of human interest in statues. At the same time, the materials used to create them (stone and metal) are not the most welcoming host environments, making them suitable for tough microbes that can harbour a few risks for human health.

Our study of European monument microbiomes was created for informational purposes. Our goal is to gain insight into the composition of these microscopic worlds, to see if and what they might have in common with nature and humans.

However, it is not designed to assess the quantity of specific microbes identified, nor to establish specific health recommendations based on the outcomes.

We learned a few things along the way. Read on to discover which monument has the largest bacterial diversity, which statues in different countries share similar traits, and why you should always wash your hands after touching them.

Monuments swabbed

| London, UK | Trafalgar Square Lions |

| Oscar Wilde | |

| Paddington Bear | |

| Sherlock Holmes | |

| Edinburgh, UK | Greyfriars Bobby |

| David Hume statue | |

| Verona, Italy | Statue of Juliet,Casa di Guilietta |

| Florence, Italy | Porcellino |

| Paris, France | Victor Noir’s Tomb |

| Buste de Dalida, Montmartre | |

| Monte Carlo, Monaco | Adam and Eve statue |

| Prague, Czech Rep. | St. John of Nepomuk Statue |

| Budapest, Hungary | Fat Policeman |

| Little Princess statue | |

| Munich, Germany | Juliet Capulet Statue |

| Sitting Wild Boar | |

| Lion Statue, Odeonplatz | |

| Hamburg, Germany | Zitronenjette |

| Stockholm, Sweden | Järnpojken Boy |

| Margaretha Krook Sculpture | |

| Amsterdam, Netherlands | The Bronze Breastplate |

| Moscow, Russia | Dog Statue at Ploschad Revolutsii |

| St Petersburg, Russia | Bank Bridge, Griboedov Channel |

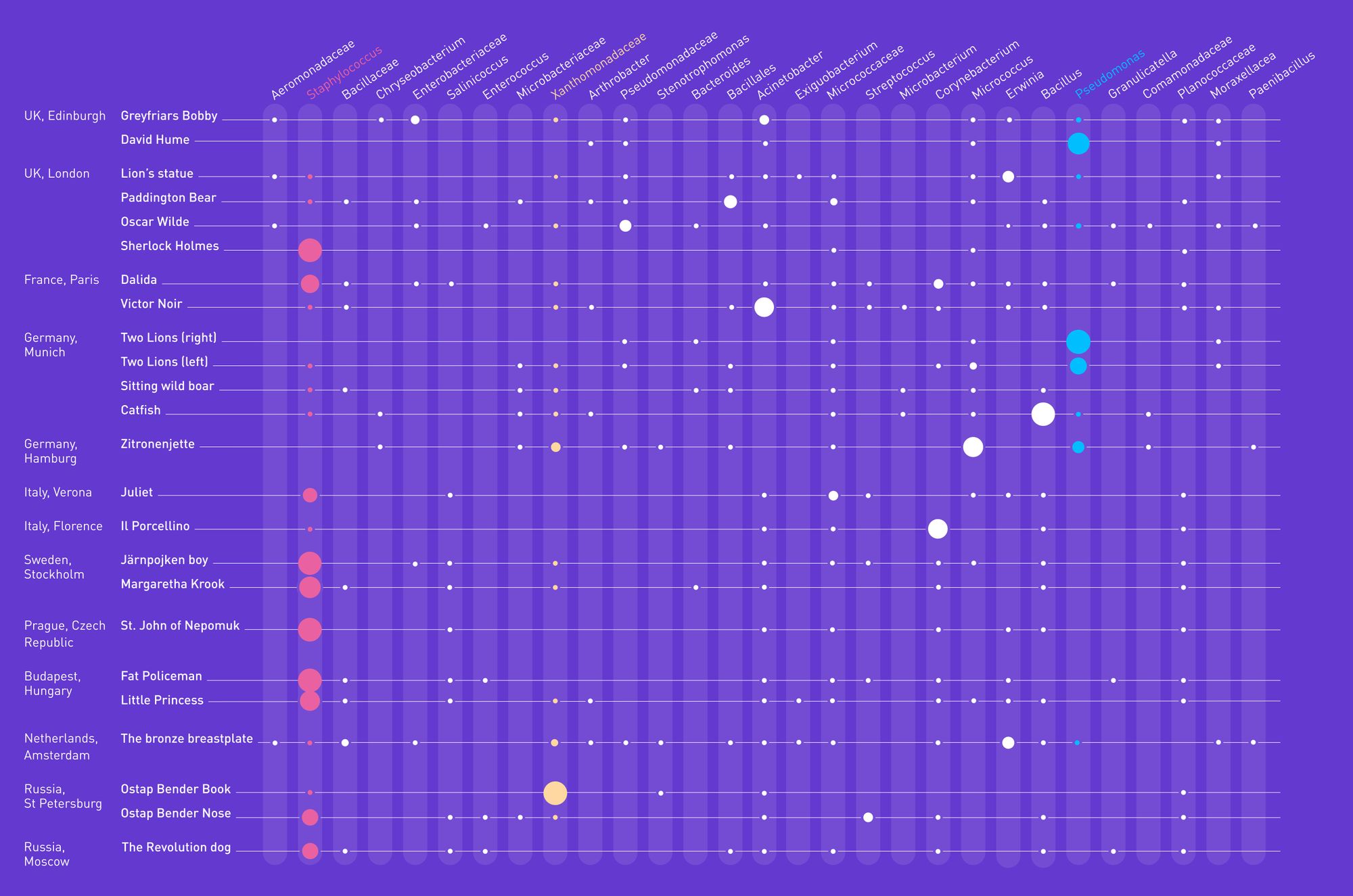

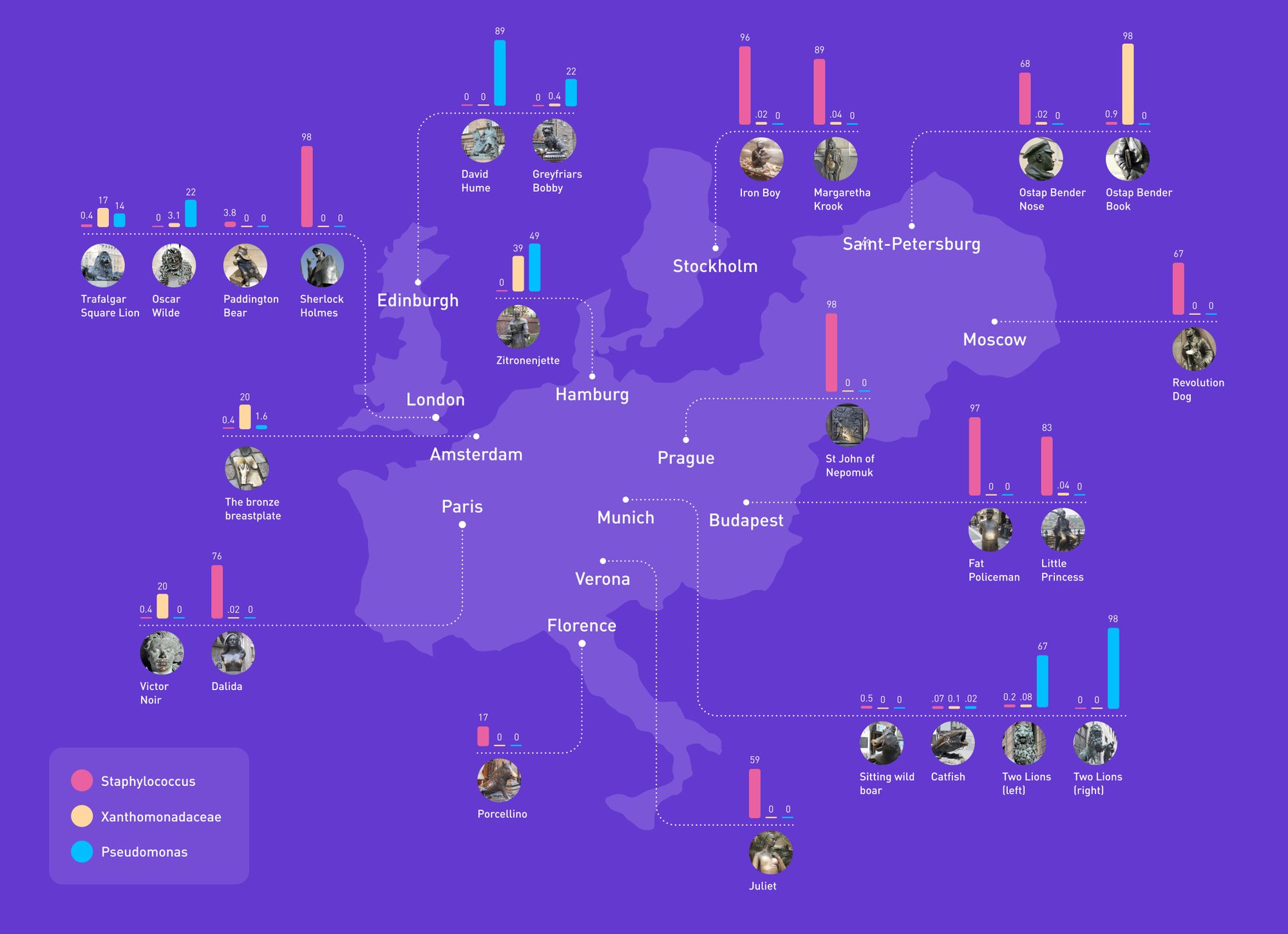

Mapping the bacteria on Europe’s monuments

We swabbed 24 statues in 13 cities located in 9 different countries in a bid to see what microscopic creatures live on these iconic structures:

Most microbes were identified

All the samples passed quality control and were subjected to computer analysis. The findings were matched to a reference database, and we were able to identify 85% of the microbial DNA.

That’s much higher than earlier studies on underground transport, probably because scientific research has progressed a lot in recent years, and a lot more microbes have been identified and categorised.

You should probably wash your hands

We found a total of 29 different bacterial genera (a classification of microbes), only 2 of which are present in the human gut microbiome (Enterococcus and Bacteroides).

Opportunistic bacteria that have the potential to make humans ill were dominant in our samples. This is not surprising, because such bacteria often live on our hands (and shoes), so they can be easily transferred through touch.

It’s important to remember that, just because a bacterium has the potential to make us ill, it doesn’t mean it will. There are a lot of factors that enter into this equation, like the quantity of bacteria present (our swab samples didn’t allow us to assess this) and how weak or strong a person’s immune system is.

Most abundant: opportunistic bacteria

| #1 Staphylococcus were found in the majority of samples. These microbes are members of the Firmicutes family and are commonly found on the skin and in the upper respiratory tract. |  |

Staphylococcus was the most abundant species found in our swabs taken from European monuments. The main concern for healthy people is conjunctivitis, better known as “pink eye”, a highly transmittable eye infection. It’s easy to treat, but it’s best to avoid.

These bacteria can also cause infections of the bladder (cystitis) and the lining of the heart muscle (endocarditis), as well as sepsis, a life-threatening reaction by the body to infection.

| #2 Pseudomonas These common bacteria are usually found in water, soil and damp areas. They are known for being able to adapt to a variety of circumstances by developing special metabolic features. |  |

Pseudomonas sp. was the second most abundant bacterial genus identified. Among other things, it’s known to cause bacteremia (the presence of bacteria in the bloodstream) and folliculitis, those unsightly red bumps that appear when a hair follicle becomes infected and inflamed.

If you have medically-diagnosed immune system problems, like immunosuppression, or open wounds, it’s better to admire from afar so they don’t compromise your health.

#3 Plant pathogens

Interestingly, we identified several types of bacteria that are recognised plant pathogens, including Erwinia sp. and Xanthomonadaceae. While it might seem insignificant, it’s a helpful reminder of how easy it is for humans to transfer deadly plant diseases from place to place.

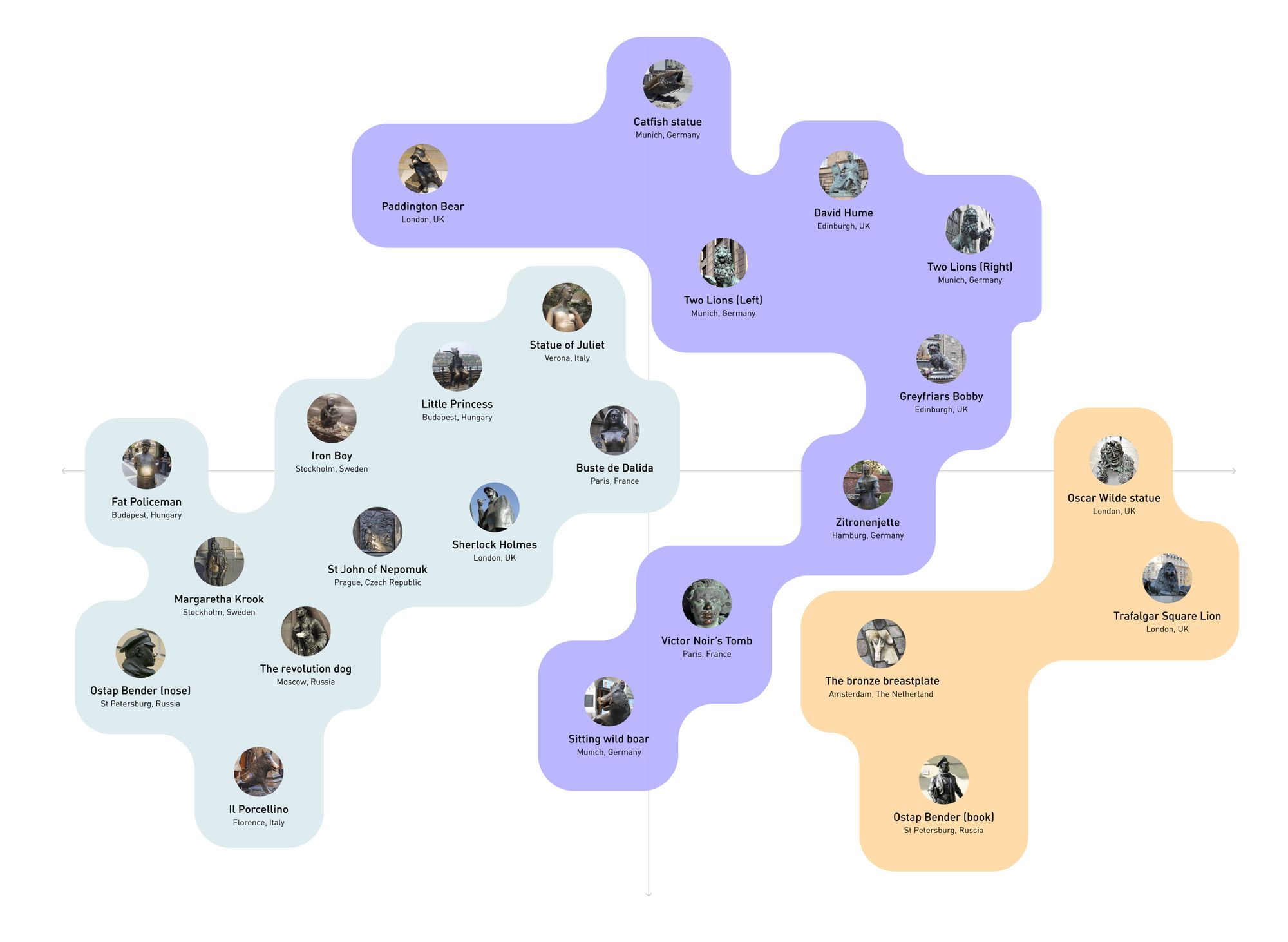

Same same, but different country

We mapped out the similarity between microbiomes of each monument to see if and what they may have in common

As you might have already guessed, passports are of no concern to bacteria. In fact, several monuments from different countries shared similar microbial signatures.

There are two lions standing guard in Munich. Yet the lion on the right had more in common with the statue of David Hume in Edinburgh than its identical counterpart. Budapest’s Little Princess was most similar to the bust of Dalida in Paris.

One similarity stood out in particular: London’s Trafalgar Square Lions shared the most in common with Amsterdam’s Bronze Breastplate that’s embedded into a cobbled street in the Red Light district. Why? Our experts surmise that it’s due to people’s feet touching these icons, rather than their hands.

The wild on Oscar Wilde

The statue of Oscar Wilde is pretty wild too

If you’re familiar with Oscar Wilde, we have a delectable tidbit for you. His statue had the most diversity. That means, when all the bacteria on all the statues were assessed, this monument had the most variety of microbial species in total. His statue, not unlike the defunct man himself, is clearly a hotspot for visitors.

A dearth in St Petersburg

People rub his nose for good luck

In contrast with Oscar Wilde, yet in a city he surely would have loved to visit (Saint Petersburg, Russia), stands a memorial to Ostap Bender, a beloved fictional character of the Soviet Union. Despite the tradition of rubbing the statue’s nose for good luck, Ostap Bender had the least diversity of bacterial species.

How to travel without trepidation

Now that you know a few facts about the bacteria, let’s break it down so you can wander with a trouble-free heart.

Humans intuitively touch their faces. A lot! Thousands of times a day. So if you are planning on visiting a statue (and possibly touching it), make sure to wash your hands properly afterwards.

We really don't recommend climbing on statues for many reasons

We also recommend you don’t put any open wounds or cuts directly in contact with these monuments. If you or loved ones have a medical condition that heightens susceptibility to infections, it’s best to admire them from a safe distance.

As we mentioned, the bacteria present on some statues indicate that shoes may be in contact with these structures too. Non-infectious health risks that involve permanent sculptures include bumps and bruises attained by climbing on them, falling off them, or banging into them.

We don’t recommend these behaviours. A human projectile will probably not harm them, but you might harm yourself. After all, holidays are always better when you’re happy, healthy and harm-free.