Trillions of tiny organisms call your gut home, but they don’t just hang out there. Instead, they carry out tasks to help keep the lining of your colon in tip-top condition.

Your gut is home to its very own microbial community, also known as the gut microbiome (or microbiota), and the bacteria inside it live in harmony with you, their host. By providing them with a home, they return the favour by keeping you healthy and helping to protect you from disease.

Up to 90% of your gut population consists of bacteria, of which there are around 1,000 different species. Of course, some bacteria are more helpful than others, and sometimes microbes can grow out of control, which is why they can make you unwell.

Table of contents

- The microbes in your gut

- The role of your gut lining

- Diet and the digestive barrier

- Lifestyle, alcohol, and exercise

The good ones, on the other hand, help keep you healthy. Certain bacteria tend to be more plentiful in healthy individuals, and their abundance in your gut is key. And you can help to boost their presence by including certain foods, particularly those rich in fiber, into your diet.

Because everyone’s microbiota is unique, yours is different from your partner’s, parents, or friends. But what remains the same is the important roles these microbes have, like breaking down nutrients from foods to make beneficial substances, and protecting your intestinal lining.

Let’s have a look at how the microbes in your gut protect your digestive barrier, why this may impact your health, and how you can actively help to increase the abundance of certain species.

What are microbes?

Bacteria are tiny organisms which can’t be seen by the naked eye. They live on and inside your body making you a walking, talking microbe nest.

Microbes are really what they say they are: micro. In fact, they are so small, they can only be seen with the help of a microscope. But they’re not only in your gut, they live all over your body, both inside and out.

A healthy gut microbiome is a rich and diverse ecosystem (like the earth)

These little living creatures can be made up of a single cell or many cells (multicellular). Because they are so small, you don’t notice them, but when they make up a large ecosystem like in the gut, they can have important consequences, both good and bad.

Your gut microbes

Your gut is home to mainly anaerobic bacteria, which do not need oxygen to survive or grow. There are up to 1,000 types of bacteria living in the intestine which are classified into different groups.

Beneficial microbes and their functions

| Bacterium | Function |

|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium | Breaks down complex carbohydrates to make useful compounds like short-chain fatty acids and vitamins. |

| Lactobacillus | Produces short-chain fatty acids like lactate and acetate, helps balance pH levels in the gut. |

| Akkermansia | Promotes a thicker mucous lining, produces short-chain fatty acids which nourish other bacteria in the gut. |

At birth, your gut was colonised by bacteria. At around the age of one, your gut microbiome would have looked similar to that of an adult, mainly thanks to the introduction of solid foods. Food choices, exercise, lifestyle, and medical history have continued to shape your microbiome since then.

Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli are two major types of probiotic bacteria which metabolise undigested foods, particularly dietary fiber. In turn, this produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) which nourish other populations of beneficial bacteria, maintain the correct acidity to deter pathogens, and prevent inflammation.

There are others too, like Akkermansia muciniphila, which munch on the mucous that lines the gut. These help to produce short-chain fatty acids, as well as encourage more mucins to be produced, ultimately thickening and strengthening the wall of the colon.

How important is your gut lining?

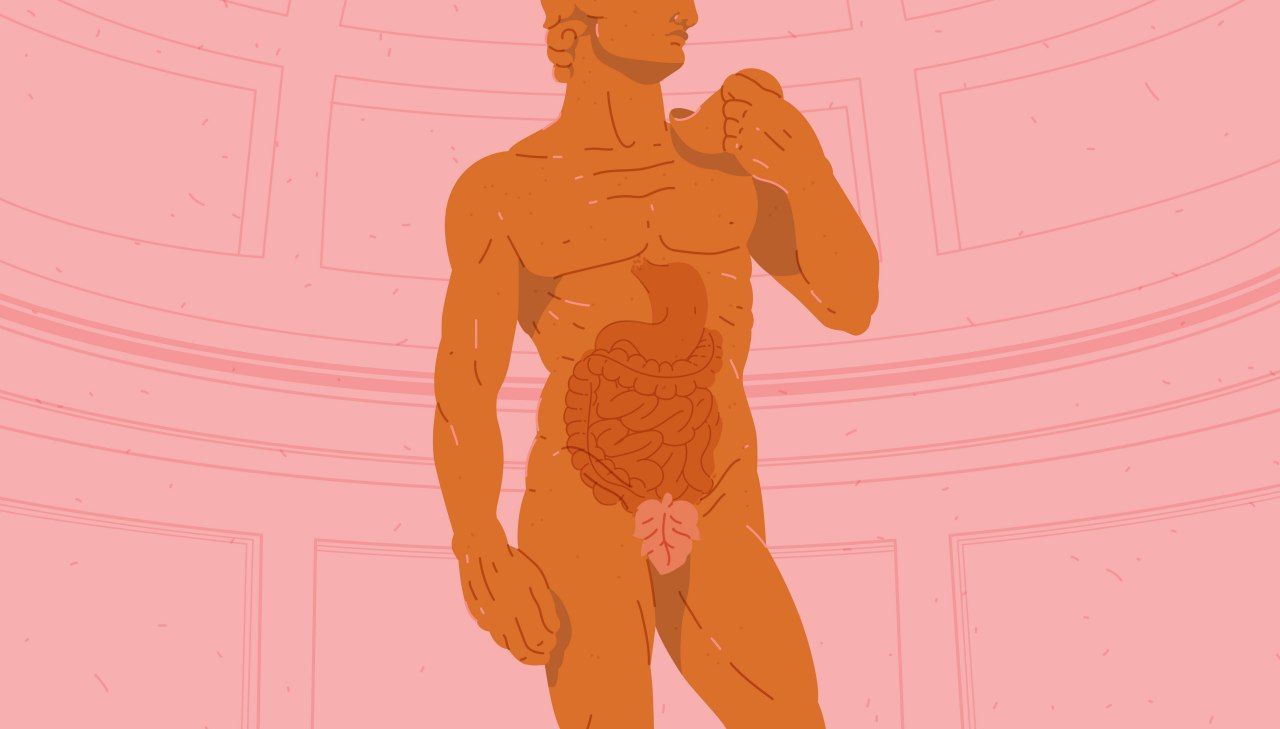

Your gut is lined with a mix of cells and mucous which collectively work together to act as gatekeepers to the rest of your body.

The health of your intestinal lining is super important. Your gut is not an impenetrable barrier because it needs to let vital nutrients and substances pass through it to reach the parts of your body which require them most. That’s where the gut lining comes in.

The gut lining has two features. It has a physical layer comprising of cells and a mucous membrane. This can be thought of as the gatekeeper because it stops large molecules getting through it.

The other is controlled by your immune system and can only be seen under a microscope. If your gut lining is threatened, your immune system will respond to the threat with inflammation, its first line of defence.

In unhealthy individuals, the lining may become too porous, allowing toxins, bacteria, and partially digested food to reach the tissues below it. This can cause inflammation and change the composition of normal bacteria in the gut.

The take-home message here is if your gut lining is healthy and intact, you’re likely to feel well and the level of inflammation in your gut should be normal. The interaction between your gut lining and the microbes residing in your gut is important, as we’re about to find out.

Diet influences your gut bacteria

Your gut is full of symbiotic bacteria that can support your health if you supply them with sustenance, like fibers from plant foods.

Plant foods are their favourite. Whole foods like vegetables, grains, fruit, nuts, and seeds are perfect examples. These foods fuel your body with energy and provide essential nutrients, but they also provide nourishment to the bacteria residing in your gut.

Foods that nourish gut microbes directly are called prebiotics. Different types of dietary fiber and polyphenols are classified as prebiotics. Our bodies aren’t well equipped when it comes to digesting complex carbohydrates like fiber, but our gut microbes have the perfect tools.

Butyrate

Some gut bacteria like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia spp., and Eubacterium rectale (members of the Firmicutes group) use prebiotics to make butyrate. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid and is the main energy source for the cells making up your gut lining (colonocytes).

When the gut isn't protected by correct nutrition and a balanced microbiome, it can become more permeable, which leads to inflammation in response to toxins, partially digested foods, and opportunistic pathogens.

Mucous-loving microbes

Another important function of butyrate is its ability to reinforce the mucous layer of the intestinal layer. The mucous layer is covered in a protein called mucin, responsible for its trademark gel texture.

For example, Akkermansia muciniphila munches on the mucins and produces short-chain fatty acids, like acetate. Microbes called Firmicutes use acetate to make butyrate. Together, these butyrate-producing bacteria and A. muciniphila increase the production of mucins which increases the thickness and strength of your gut lining.

Diet, microbes, and gut lining health

If your gut bacteria are happy and well-fed, your gut lining will be healthy and ready to protect you.

So, what happens if your gut lining isn’t working properly? It might become too porous, and this can be a problem because it lets things through that usually wouldn’t. If microbes, their metabolites, or food get through this barrier, it may affect your health.

Your gut follows a finely tuned rhythm that can be easily disturbed

When you digest food, tight junction proteins of the gut lining stretch, allowing nutrients to pass into the body. This is called intestinal permeability (or "leaky gut"), it causes a little inflammation, and it's completely normal.

However, if the intestinal barrier is too porous or stays open for too long (like if you’re snacking non-stop), then toxins, bacteria, and food can leak through the gut lining, causing your immune system to be constantly stimulated and lead to chronic inflammation.

Diet and “leaky gut”

Diet can have an important influence on how well your gut lining works, and your gut microbes love dietary fiber. So, a diet low in fiber can mean your good bacteria are not well nourished, preventing them from doing important jobs like producing butyrate and nutrients.

Equally, diets which are high in saturated fat have been shown to reduce the abundance of Lactobacillus. These probiotic microbes nourish other bacteria in the gut and keep the acidity of the gut stable. Acidity deters pathogens and encourages the growth of your commensal bacteria.

But it’s not just fiber that’s important. Deficiencies in some nutrients, like vitamin A and D, zinc, or magnesium can increase the permeability of the intestinal lining. Many of these nutrients are also reduced in chronic diseases like obesity.

Fundamentally, the western diet is considered a significant factor in poor gut function. The diet is high in saturated fat and sugar, which reduces the abundance of commensal and beneficial bacteria and negatively impacts the integrity of the gut lining.

Lifestyle and gut health

Gut microbes have a surprisingly uncomplicated relationship to our lifestyle. They benefit from exercise, but not so much from alcohol.

Alcohol

Just like diet, alcohol can affect the composition of the gut microbiome. Dysbiosis is a consequence of drinking alcohol on a regular basis, so too is bacterial overgrowth, which happens when some types of normal bacteria become overabundant in the gut.

Dysbiosis, including bacterial overgrowth, have been linked to the development of alcoholic liver disease and cirrhosis. Individuals who drink chronically have an increased abundance of Proteobacteria and a decreased abundance of Bacteroidetes.

However, even though alcohol can cause dysbiosis, some alcoholic beverages contain polyphenols, natural compounds found in plant-based foods. Polyphenols have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties.

One study shows the effects on the gut microbiota by polyphenols. Participants were fed 272ml of red wine per day, 272ml of dealcoholised red wine per day, or 100ml of gin per day. Both red wine and dealcoholised red wine increased the abundance of Bifidobacteria in the gut.

The consumption of gin, however, increased the abundance of Clostridia, whereas both types of red wine decreased its abundance. The polyphenols in red wine could therefore help prevent the growth of Clostridia, which may increase the risk of colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease.

Exercise

Exercise has a variety of benefits for your health and it enriches your gut microbiota. Daily moderate activity can increase the abundance of Firmicutes, members of which are known to promote a healthy gut environment, like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a microbe that produces butyrate.

Plus, some studies have shown that fit individuals have a gut microbiome rich in butyrate-producing bacteria, an indicator of good gut health. Increased diversity of bacteria in the gut is a positive thing, and because exercise can contribute to it, there’s even more reason to get more active.

Exercise has also been shown to have effects on female gut microbiomes. For example, women who participated in exercise continually, even at low doses, have a greater abundance of health-promoting bacteria like Bifidobacteria, F. prausnitzii, and A. muciniphila.

Aerobic exercise or cardio is a great way to keep fit, and it has benefits for your microbiota. Types of activity that fall into this category include walking, dancing, rowing, and cycling.

If you’re just starting out on your cardio journey, you may not be able to sustain your effort for a long period. But that’s ok. You can build on this the more you exercise. Remember, some exercise is better than none at all.

Remember this

At first glance, the thought of bacteria inside you might be scary, but the commensal bacteria in your gut are actually your friends. This mutual relationship has benefits for them and your health.

Many microbes make light work of fermenting carbohydrates into beneficial products, like butyrate. Butyrate is an energy provider for the cells lining your gut. As their prime energy source, butyrate enables these cells to do their job properly.

You can increase the abundance of Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli by incorporating the right foods into your diet. Eating lots of fiber, which your gut bacteria love, means they can break it down into beneficial short-chain fatty acids and vitamins which you need to thrive.

And then there’s bacteria like A. muciniphila who munch on the mucins in your gut, encouraging your cells to make more. By making more mucins, the mucous lining your gut is thicker and stronger, preventing opportunistic bacteria from causing you harm.

Your gut bacteria have a fundamental role in keeping your gut lining healthy and fully-functioning. By eating a diet rich in fiber and getting some exercise, you can keep them nourished and ensure they keep you protected and full of life!

☝️TIP☝️Discover your gut bacteria and their functions with the Atlas Microbiome Test and get 10% off when you sign up for blog updates!

- Engen, P. A., Green, S. J., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2015). The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol research : current reviews, 37(2), pp 223–236.

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2016). Can Gut Bacteria Improve Your Health? Harvard Medical School.

- Liu, H et al. (2018). Butyrate: A Double-Edged Sword for Health? Advances in Nutrition: 9(1), pp 21-29.

- Monda, V et al. (2017). Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid Cell Med Longev.

- Mu, Q et al. (2017). Leaky Gut As a Danger Signal for Autoimmune Diseases. Front Immunol: 8.

- Odenwals, M, A and Turner, J, R. (2016). The Intestinal Epithelial Barrier: A Therapeutic Target? Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology: 14, pp 9-21.

- Schroeder, B, O. (2019). Fight Them or Feed Them: How the Intestinal Mucus Layer Manages the Gut Microbiota. Gastroenterology Report: 7(1), pp 3-12.

- Toribio-Mateas, M. (2018). Harnessing the Power of Microbiome Assessment Tools as Part of Neuroprotective Nutrition and Lifestyle Medicine Interventions. Microorganisms: 6(35).

- Zhang, Y, J et al. (2015). Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci: 16(4), pp 7493-7519.