Emerging evidence suggests that an imbalance in the microbiome may contribute to IBS development via the gut-brain axis. We explore the link between gut bacteria and IBS before surveying the evidence for probiotics and faecal transplants in IBS treatment.

Table of contents

- IBS causes: a disorder of the gut-brain axis

- The gut microbiome, dysbiosis and IBS development

- Following the clues

- IBS treatments targeting the gut microbiome

- Faecal microbiome transplant

- Probiotics

- Summary

IBS causes: a disorder of the gut-brain axis

IBS is a functional bowel disorder characterised by chronic, relapsing symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation, bloating and distension.

Researchers categorise IBS into four main sub-types according to the predominant symptom. The four types are:

- IBS- D (Diarrhoea)

- IBS- M (Mixed)

- IBS- C (Constipation)

- IBS- U (Unclassified)

Researchers are unsure of the exact causes behind the disorder, though genetics, gastrointestinal infections, chronic inflammation and emotional trauma are potential factors.

Moreover, IBS symptoms appear to result from abnormal gut motility (muscle contractions) and visceral hypersensitivity, meaning an increased pain response to gas, food and movement in the intestines.

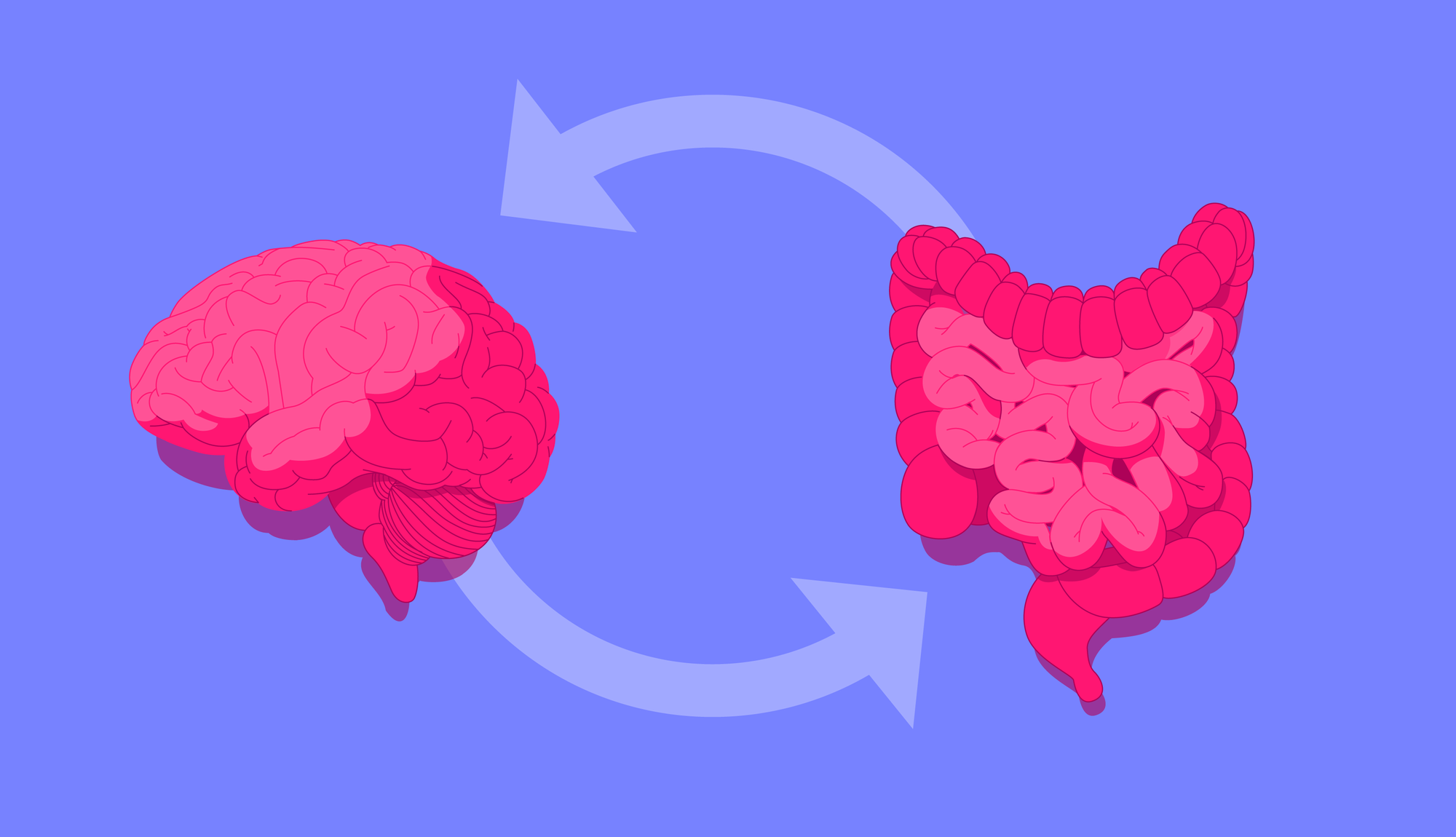

The gut-brain axis is a bi-directional communication network between the brain and the gut, acting via the vagus nerve, enteric nervous system and the central nervous system.

According to the most popular model of IBS etymology, disruptions to the gut-brain brain axis are responsible for altered gut motility and sensitivity.

In short, stress can disrupt the enteric nervous system in your gut, known as the “second brain”, hindering digestion and triggering IBS symptoms. Likewise, a troubled gut also appears to send messages to the brain, potentially influencing mood.

Likewise, it elucidates why psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy can improve symptoms; if our two brains “talk” with one another, therapies that help one should help the other.

The gut microbiome, dysbiosis and IBS development

Emerging evidence suggests that an imbalance in the microbiome (dysbiosis) may contribute to IBS development via the gut-brain axis.

The prevailing hypothesis is that an imbalance in the gut bacterial community compromises the gut lining, activating the gut immune system and triggering low-grade chronic inflammation. In turn, this can cause impaired gut motility and visceral hypersensitivity.

On the contrary, an imbalanced microbiome is associated with increased intestinal permeability (leaky gut), low-grade chronic inflammation and increased intestinal sensitivity.

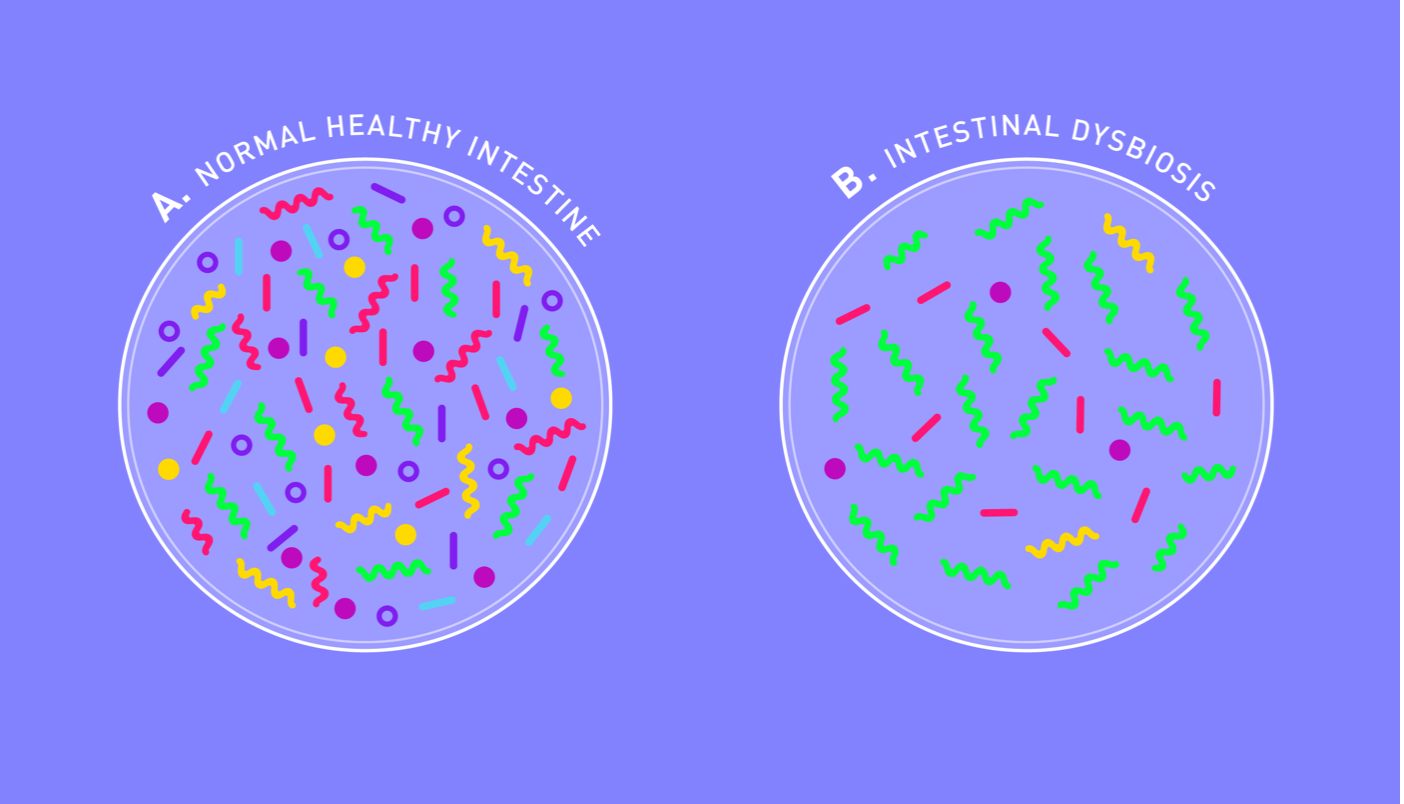

If you imagine a healthy microbiome as a flourishing garden where weeds are kept in check, a dysbiotic one would be a scorched lawn overrun by invasive species.

Dysbiosis occurs when microbiome diversity is depleted, and pro-inflammatory bacteria predominate. Numerous factors can contribute to this state of affairs, including diet, excessive antibiotics and stress.

Following the clues

There is plenty of evidence to support the role of gut bacteria in IBS development. Firstly, as many as 6-17% of IBS sufferers can trace IBS onset to an acute bout of gastroenteritis, whether bacterial, fungal or parasitic.

This phenomenon has spawned a whole new subtype of IBS called Post-Infection IBS (PI-IBS). Often, the condition begins after a bacterial infection by species such as:

- Clostridium difficile

- Campylobacter

- Salmonella

- Shigella

Interestingly, PI-IBS is defined by dysbiosis in the gut microbiome. For example, those with PI-IBS have been observed to lack butyrate-producing probiotic bacteria in the gut.

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that can reinforce the intestinal lining and combat inflammation. A gut depleted of these short-chain fatty acids can become compromised, allowing pathogenic bacteria into the bloodstream.

For example, at least one study has observed reduced diversity and richness in the bacterial communities of IBS-D sufferers.

Similarly, a systematic review and meta-analyses of case studies concluded that IBS-D and IBS-C are characterised by dysbiosis in the gut microbiome. According to the study, IBS sufferers were found to have lower levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium compared to healthy controls. Parallel to this, the IBS microbiome was slightly enriched in Escherichia coli.

Furthermore, a study in the Journal of Gastroenterology identified a microbial signature that could predict severe IBS, suggesting that our gut bacteria play a role in the development of functional bowel disorders.

The severe IBS signature was characterised by reduced diversity and enrichment with Clostridiales or Prevotella bacteria species. Based on this, the team were able to discriminate between IBS patients with severe symptoms, mild/moderate symptoms, and healthy control subjects.

Last but not least, a study published in the American Journal of Microbiology sequenced the microbiomes of 490 individuals to explore potential patterns.

The IBS microbiomes were enriched in gram-negative bacteria and contained fewer butyrate-producing species than healthy controls.

As we touched upon earlier, butyrate is an anti-inflammatory short-chain fatty acid produced when our gut bugs feed on prebiotic fibres.

The link between the microbiome and IBS is further supported by animal studies, particularly on mice. Tellingly, researchers have induced IBS-like symptoms by transplanting the microbiome of humans with diarrhoea-predominant IBS into mice.

After the faecal transplant, the mice exhibited altered gut motility, intestinal barrier dysfunction, innate immune activation, and anxiety-like behaviour.

IBS treatments targeting the gut microbiome

In light of this evidence for an IBS-microbiome connection, numerous clinical trials continue to explore IBS treatments that target the gut microbiome.

Most notably, ongoing clinical trials are examining the use of probiotics and faecal transplants in treating IBS. Overall, these studies have shown some promise, despite variability in the results.

Faecal microbiome transplant

In a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled study, researchers tested the efficacy of a healthy faecal transplant in 55 patients with diarrhoea predominant IBS.

Whilst 43% of the placebo group reported significant symptom improvement (12 of 28), 65% of the study group saw improvement after three months. (36 of 55). In other words, altering the gut-microbiome in IBS-D triggered symptom improvement, reinforcing a connection between gut bacteria and IBS development.

Similarly, another double-blind, placebo-controlled study comprising 165 subjects uncovered equally promising results.

Once again, participants were split into two groups, one receiving a placebo and the other group healthy faecal samples in capsule form. Overall, only 23.6% of the placebo group reported improvements in quality of life. In comparison, 89.1% reported the same improvements in the active group!

With that said, one double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT has reported no symptom relief in IBS-D patients after 12 weeks compared to placebo.

Likewise, a similar study on patients with moderate-severe IBS observed more significant symptom improvement in a placebo group, despite the FMT group showing marked changes in microbiome composition.

Due to the variability in results, some researchers have posited that IBS is a catch-all term for multiple diseases or subtypes, all of which have the same symptoms.

Despite the variable results, FMT shows promise as a potential treatment for IBS, particularly the diarrhoea-predominant sub-type. With that said, more large-scale, high-quality studies are needed to ascertain the potential risks and long-term efficacy of the treatment.

Probiotics

Probiotics are live, beneficial microorganisms that can improve human health when consumed. Clinical trials studying the effect of probiotics on IBS report modest but statistically significant benefits compared to placebo.

Firstly, the American Journal of Gastroenterology performed a meta-analysis on 30 studies looking at probiotics in IBS treatment.

Likewise, a systematic review in the BMJ looking at 19 RCTs found promising results favouring probiotics as an IBS treatment. In 15 of these trials, probiotics outperformed placebos at improving IBS symptoms, though the paper cautions that the extent of these benefits and most effective strain/species remains unclear.

Last but not least, the probiotic Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly reduced IBS symptoms in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study.. Likewise, B. infantis 35624 has also shown promise in treating IBS.

Summary

- Research suggests that IBS is caused by disruptions in the gut-brain axis, a two-way communication highway connecting the brain and enteric nervous system

- Emerging evidence implicates our gut microbiota in IBS development

- 6-17% of IBS sufferers can trace their symptoms back to a gastrointestinal infection

- Researchers have identified alterations in the stability and diversity of the microbiome in IBS patients, including a signature for severe IBS

- Manipulating the microbiome of mice produces IBS type symptoms such as altered gut motility and intestinal permeability

- Treatments that target the microbiome show small but statistically significant benefits for IBS symptoms

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.