Gut bacteria shape human health in various ways, supporting immune function, communicating with the nervous system and metabolising anti-inflammatory compounds, but could they also be the key to better mental health? Keep reading to find out.

Table of contents

- The gut-brain-microbiota axis

- Microbiome and mental health: following the clues

- How does the microbiome influence mood?

- Psychobiotics: probiotics for the mind

- Food and mood: is a balanced diet the ultimate psychobiotic?

- The key takeaways

The gut-brain-microbiota axis

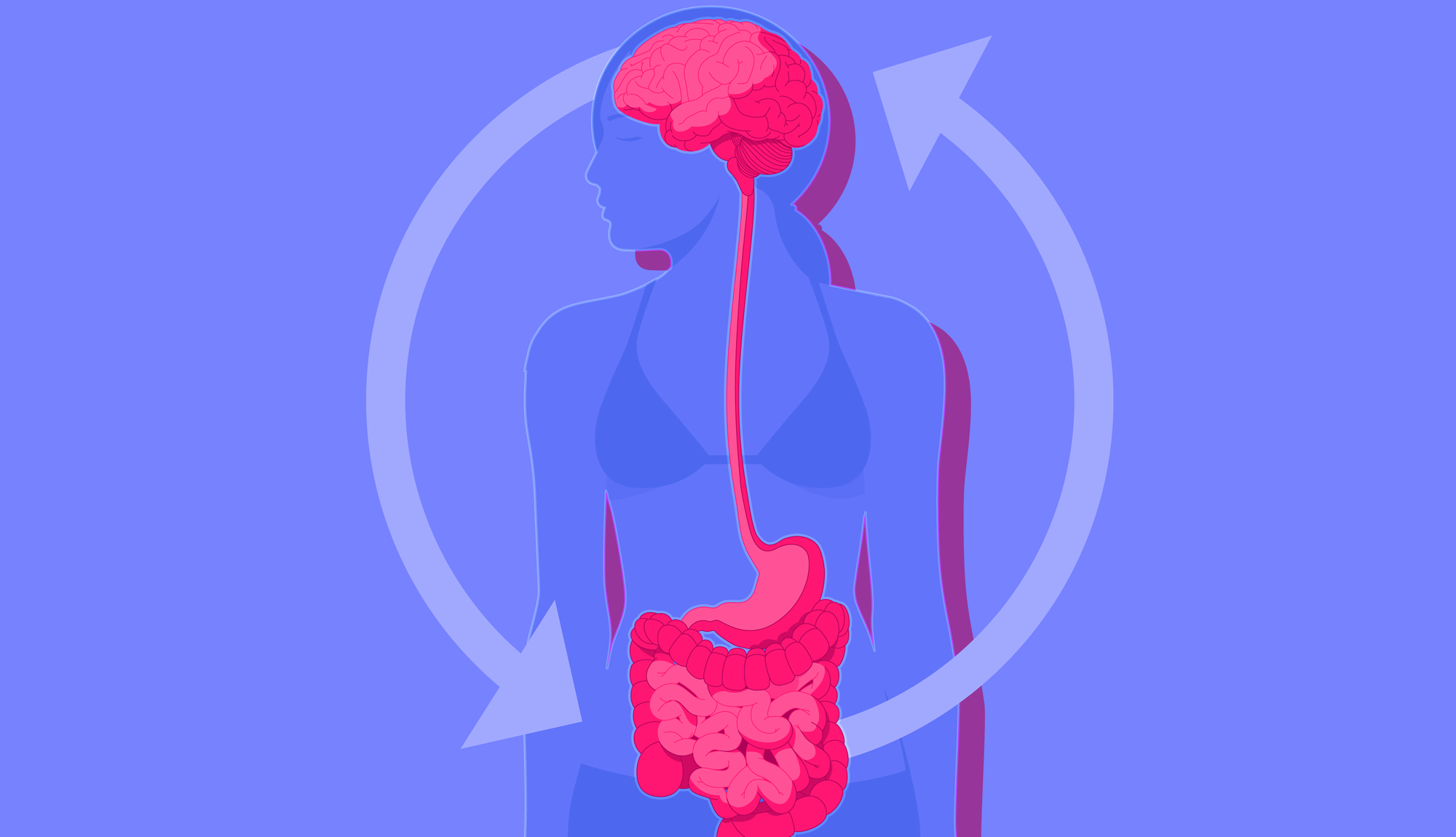

The gut and brain maintain constant two-way communication via multiple pathways, prime among them the vagus nerve.

Known as the gut-brain axis, this communication network links the emotional and cognitive centres of the brain with peripheral intestinal functions.

Likewise, stress can manifest through digestive issues, as anyone who has experienced "butterflies in the stomach" will attest. In practice, this means that a troubled gut can lead to a troubled mind and vice versa.

Emerging research suggests the gut microbiome may be able to communicate via the gut-brain axis, thereby shaping our mood for better or worse.

Whilst higher quality human trials are needed to elucidate the connection, few in the field of microbiome research would deny that there is a link between mental health and gut bacteria.

Microbiome and mental health: following the clues

When investigating what causes a condition, you often must follow the clues like a detective, narrowing down your suspects.

As we shall explore now, the microbiome appears to be implicated in numerous mental health conditions, including depression.

Firstly, those with mental health conditions, including depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, often have microbiomes characterised by imbalance and increased intestinal permeability. By itself, it's not enough the implicate our gut bugs, but it hints at a link.

More tellingly, mice transplanted with the microbiota of depressed individuals adopt behaviours characteristic of their donors, implying a causative relationship between the microbiome and mood disorders.

Furthermore, a pivotal study found that mice raised in a sterile environment, therefore lacking a microbiome, show exaggerated physiological responses to stress.

The exaggerated stress response was reversed when the mice were given specific probiotics, further implicating the microbiome.

How does the microbiome influence mood?

The pathways by which our gut bacteria may influence mental health are not fully elucidated, but animal and human studies suggest several mechanisms.

Firstly, a dysbiotic microbiome, characterised by imbalance and reduced diversity, is positively associated with inflammation.

In short, a dysbiotic microbiome increases intestinal permeability, allowing bacteria to escape into the bloodstream via the gut.

Tellingly, many mental health conditions are characterised by increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood.

For example, those with depression have been observed to have higher levels of inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).

What's more, injecting pro-inflammatory cytokines can induce depression in human patients.

How do we know this? Interferon-α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, was once the standard treatment for hepatitis C in humans, though it was displaced due to its side effects, among them low mood.

Connecting these dots, it is hypothesised that disruptions to the microbiome increase intestinal permeability, allowing bacteria to escape into the bloodstream. In turn, inflammatory cytokines proliferate, penetrating the blood-brain barrier and impacting mood.

Additionally, microbial metabolites, particularly short-chain fatty acids like butyrate, are thought to be neuroactive.

Lastly, experimental findings in animals and humans suggest that gut microbiota can modulate the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis (HPA Axis), a key part of the body's fight-or-flight stress response.

Firstly, a dysbiotic microbiome can trigger the HPA axis to produce Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF). CRF is a precursor to cortisol, the stress hormone behind our body's fight-or-flight response.

HPA dysregulation is widely observed in patients with mental health conditions, alongside disruptions in microbiome diversity.

Moreover, gut bacteria can reduce the HPA axis response by releasing anti-inflammatory metabolites such as butyrate.

The relationship between the HPA axis and microbiome appears to work in both directions, with HPA activation influencing microbiome diversity.

As you can see, the cumulative evidence strongly suggests a microbial component in numerous mental health disorders.

☝TIP☝ With an Atlas Microbiome Test, you'll discover which bacteria you have, which you need and how to cultivate those you need. Among 22 health reports, you'll also learn the inflammatory potential of your gut bugs!

Psychobiotics: probiotics for the mind

Assuming a link between the microbiome and mood, researchers are increasingly hopeful that we can eventually treat mood disorders with probiotics, spawning a new discipline known as psychobiotics.

Psychobiotics are bacterial cultures that benefit mental health through interactions with the microbiome.

The research for psychobiotics to date is primarily confined to rodents, while the few human studies available have furnished mixed results.

Animal studies

In one study, researchers tested whether the probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis could minimise stress in rat pups.

As you would expect, mice pups separated from their mothers experience an intense stress response, including higher cortisol levels and inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6.

Interestingly, mice pups fed B. infantis exhibited reduced stress response, comparable to the effect of common antidepressants like citalopram.

Previously, the bacterial strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 have been observed to downregulate the HPA axis in mice pups after maternal separation also.

In another study, Christopher Lowry, an associate professor of integrative physiology at the University of Colorado Boulder, explored how heat-killed Mycobacterium vaccae, (shown to have anti-inflammatory properties), would affect mice stress responses.

In order to trigger a stress response, Lowry and his colleagues housed the mice with a dominant aggressor mouse. Usually, mice caged with a belligerent bully exhibit submissive behaviour and develop colitis, an inflammation of the colon.

But not so with the mycobacterium treated mice; these little critters showed reduced levels of inflammation and submissive behaviour compared to a control group. Additionally, they were also bolder when navigating a stress-inducing maze.

In other animal studies, probiotic supplementation has been observed to reduce depressive behaviour and alter the levels of circulating neurotransmitters in mice.

So, could psychobiotics similarly affect humans, minimising our stress response and improving mental functioning?

Human studies

According to one study, bipolar patients with higher levels of circulating cytokines had higher readmission rates than those with less inflammation within six months of release.

Intrigued by these results, Dickerson et al. designed a randomised controlled trial to see if anti-inflammatory probiotics may exert an influence.

To this end, she gave 33 patients hospitalised for mania strains of bacteria shown to have anti-inflammatory properties, namely Lactobacillus rhamnosus (strain GG) and Bifidobacterium animalis lactis (strain BB-12). The other half were given a placebo.

After six months, only 8 of those given probiotics were readmitted compared to 24 of those in the placebo group.

While it is tempting to get excited, the study did not measure microbiome diversity directly, though the researchers hypothesised that microbial changes were behind the observed effects.

After creating criteria for inclusion, they screen the studies for bias, eliminate studies that don't qualify and then summarise the aggregate findings of the research.

In some cases, they also perform a meta-analysis, meaning they perform a statistical analysis of multiple studies to calculate an "overall effect."

In 2015, a research duo conducted a systematic review of studies testing the efficacy of psychobiotics. Only ten trials met their inclusion criteria, all double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trials.

The trials included were a mixed bunch, testing the effect of multiple probiotic strains on various psychological outcomes, including mood, anxiety, stress, autism and schizophrenia.

Overall, the study found "very limited" evidence for the efficacy of psychobiotics, with only one trial finding moderate improvements in anxiety and depression scores.

The authors acknowledge that it would be problematic to interpret the results cohesively given the variability in population size, bacterial strains used, and the psychological outcome observed.

In light of this, they called for more randomised controlled trials into the effectiveness of psychobiotic going forward.

Seeking to narrow the research focus, a research team undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychobiotic interventions for anxiety in youths.

Fourteen studies were deemed eligible for systematic review, while 10 met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis- all of the studies were randomised trials on human subjects.

Overall, the study found "limited" evidence for psychobiotics in anxiety treatment, with the most pronounced effects seen in those with high anxious traits.

The paper notes that their results are far from conclusive, cautioning that psychobiotic research is very much in its infancy. Once again, the dose and strains of bacteria varied widely across the studies.

More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomised controlled trials found that psychobiotics can exert significant anti-depressant-like effects on those with clinical depression.

The paper, published in the Journal of Functional Foods, also found that multi-strain psychobiotics showed a more significant antidepressant effect than single-strain antibiotics, as did solid capsules over liquid psychobiotics.

Caution is necessary

An enduring challenge facing psychobiotic researchers is that we all have unique microbiomes. Moreover, beyond balance and diversity, it is still unclear what constitutes a healthy microbiome.

Most likely, there are multiple types of "healthy" microbiome, just as there are a variety of ecosystems on planet earth; a healthy jungle ecosystem is vastly different from a healthy arctic ecosystem, though both are stable and allow species to thrive.

With this in mind, future probiotics may need to be tailored to people's microbial communities, which will be expensive and time-consuming to develop.

But before you get demoralised, there is an accessible and straightforward way you may be able to shape your mental health via the gut, starting today.

Food and mood: is a balanced diet the ultimate psychobiotic?

Diet is a powerful determinant of microbiome composition, able to shape the communities of bacteria in your gut for better or worse.

In particular, the Mediterranean diet, rich in plant-based fibre, fruit, legumes, nuts and seeds, shows potential in the treatment of depression.

So what's the secret behind the diet? The Mediterranean diet is rich in prebiotic ingredients, meaning food known to encourage the growth of beneficial bacteria.

When you consume these foods, your human enzymes struggle to break them down, meaning they pass undigested to the large intestine.

Once there, the trillions of bacteria in your gut get to work fermenting these resistant carbs like piranhas, burping out anti-inflammatory compounds such as butyrate.

Prebiotics are like fertiliser for your beneficial bacteria and can help boost diversity and promote overall intestinal health.

According to research at the Alimentary Pharmabotic Centre (APC), University College Cork, those who report improved mental health due to dietary changes also show changes in their gut microbiome.

In a 2016 paper published in the Trends In Neuroscience Journal, Ted Dinan, the man who coined the term psychobiotics, argues that prebiotics should be encompassed in the definition of psychobiotics.

Better still, the Mediterranean diet is linked with a long and impressive list of health benefits, including a reduced risk for obesity, heart disease, stroke and all-cause mortality.

☝TIP☝ With an Atlas Microbiome Test, you will receive weekly, personalised food recommendations to help cultivate microbiome diversity and optimise your overall health.

The key takeaway

Experimental research in both humans and animals has revealed a link between the microbiome, brain functioning and mental health.

The mechanisms by which microbes may influence mood are not fully elucidated, though animal and human studies suggest three plausible pathways.

Firstly, research suggests that imbalance in the microbiome can increase intestinal permeability, thereby allowing inflammatory cytokines to penetrate the blood-brain barrier.

It is interesting to note that dysbiosis and inflammation are widely observed in multiple mental health conditions.

Secondly, the microbiome plays a key role in the development of the HPA axis, a key hormonal component in the body's stress response.

What's more, the microbiome can both activate and reduce the HPA axis response, depending on its composition.

HPA dysregulation is common in conditions such as depression and schizophrenia, suggesting another pathway by which microbes may influence mental health.

Lastly, the microbiome is known to manufacture multiple mood-altering neurotransmitters, including GABA, serotonin and dopamine.

In light of this connection, researchers are hopeful that we can treat mental health conditions with probiotics, spawning the term "psychobiotics".

The research on psychobiotics is largely confined to rodents, with numerous studies demonstrating that probiotics can influence behaviour, stress response and inflammation in mice models.

The few human studies available have furnished mixed results, though at least one systematic review suggests that specific probiotic strains can exert antidepressant effects in clinically depressed patients.

There are numerous challenges facing researchers as they try to develop psychobiotics. For a start, different people may respond to probiotics in unique ways depending on their microbiome composition.

With this in mind, the future of psychobiotics may involve personalised treatments which will take time and money to develop. A far cheaper and more accessible psychobiotic may be available through dietary changes.

In short, prebiotic foods act like fertiliser for the microbiome, increasing levels of beneficial gut bacteria. Examples include:

- chicory root

- Jerusalem artichoke

- ginger

- asparagus

- bananas

- onions

Ted Dinan, the man who coined the term psychobiotics, argues that the term psychobiotics should incorporate prebiotics also.

Tellingly, the Mediterranean diet is associated with improved mood and reduced cognitive decline.

Parallel to these benefits, the diet has been observed to increase microbiome diversity, leading researchers to suggest they are modulated by gut bacteria.

Pending further studies on the efficacy of psychobiotics, we recommend you focus on eating a balanced diet rich in prebiotic fibre.

Whilst nutritional psychiatry should not replace traditional therapies for mood disorders, namely antidepressants and cognitive behavioural therapy, it should not be ignored.

Evidence suggests that what we put in our mouths can change our mental well-being for better or worse. In light of this, food should be considered a complementary or alternative treatment for mood disorders.

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.