The microbiome is central to human health, even playing a key role in the education of the developing immune system. But where does our microbiome come from, and how do we acquire our gut bacteria? In this article, we explore the origins and development of the microbiome in early life, including how to nurture a growing microbiome.

Table of contents

- Humans and the gut microbiome: partners in health

- Thank Mum for your microbiome

- The first three years: a time of flux

- Breastfeeding: microbiome fertiliser

- Puppy power: pets and microbiome diversity

- Rubbing off on each other

- How to nurture a growing microbiome

- Key takeaways

Humans and the gut microbiome: partners in health

Whilst we may not be able to see it, the world is teeming with bacterial life- in the air, soil, water, you name it. Bacteria even thrive in the world's most extreme environments, including at the bottom of the Mariana Trench and near hydrothermal vents.

Humans are no exception, playing host to a bustling community of bacteria in and on our bodies. Comprising 1 to 3 % of our body mass, our bacterial sidekicks outnumber our human cells 10 to 1, dwarfing the human genome.

For comparison, the human genome contains around 23,000 genes, compared to the 3.3 million bacterial genes that make up the human microbiome!

The largest and most important community of bacteria resides in the colon, collectively known as the gut microbiome.

Humans, alongside all mammals, co-evolved with bacteria over millions of years, meaning some of the body's most essential functions depend on microbial assistance.

Far from hitchhiking, gut bacteria are critical for human health, with research suggesting they can influence mood, metabolism, cholesterol levels and immune function.

During your formative years, the microbiome plays a vital role in the infant's immune "education",teaching it to attack pathogens and spare benign bacteria.

In short, a diverse microbiome means that your immune cells receive a broad education. On the contrary, a compromised microbiome can mean your immune cells have gaps in their knowledge, which may later translate to immune dysfunction.

Research suggests that disruptions to the microbiome during our early years may increase the risk of autoimmune disorders and allergies.

In particular, birth by caesarian section, bottle-feeding, and excessive antibiotic use adversely alter the balance and diversity of a child's microbiome, hindering immune education.

Given the importance of the microbiome to human health, you may be wondering how we come to acquire our bacterial sidekicks.

Join us as we trace the origins and development of the human microbiome (Spoiler alert: it's been with you since the beginning!).

Thank Mum for your microbiome

An unborn foetus is cocooned in the safety of a sterile womb, shielded by the amniotic sac. At this point, the child's cells are 100% human, but it's the last time it'll be able to call every cell its own.

After nine months, the amniotic sac is ruptured before or during labour, at which point a flood of bacteria rapidly colonises the foetus.

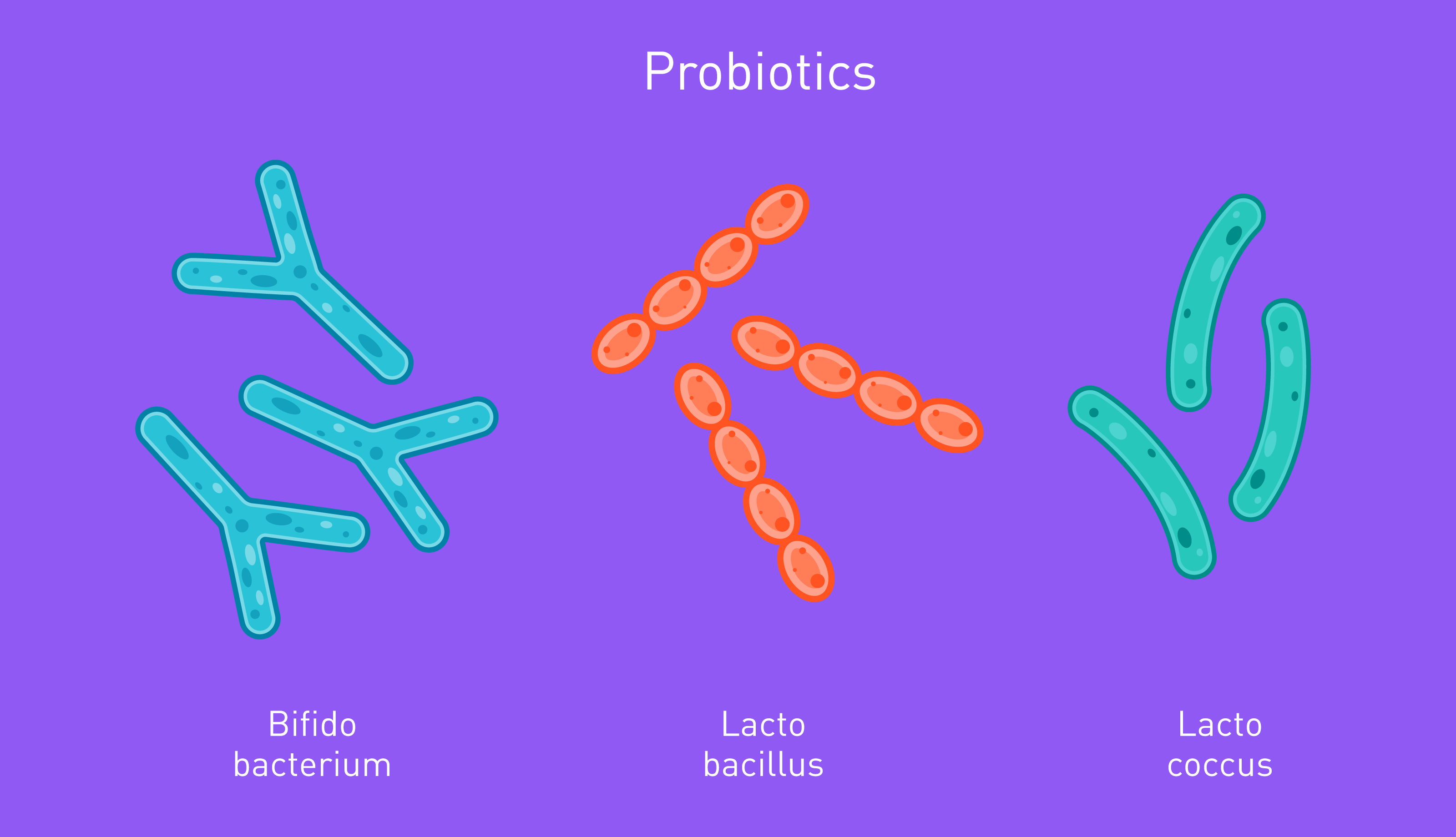

Upon exiting the vaginal canal, the child is coated in a film of microbes, predominately comprised of lactobacillus bacteria.

Within hours, the child's human cells are outnumbered by bacteria cells, which reproduce astonishingly quickly. The microbiome is born, and it might be the best birthday present you ever receive!

How you are born shapes your initial microbiome composition; for example, children born via the birth canal are colonised by a mixture of their mother's vaginal, faecal, and skin bacteria, alongside a few resilient microbes from the hospital and nurses.

The extent to which this impacts later health is up for debate, though research suggests children born via c-section may be at a higher risk for autoimmune conditions and allergies.

In light of this, some suggest swabbing surgically born babies with vaginal microbes, a process coined bacterial "seeding".

The renowned microbiologist Robert Knight opted to do so when his daughter was surgically delivered, although the efficacy and safety of this method are disputed.

More recently, experts have raised concerns it could spread diseases to the child.

In response to the growing popularity of bacteria seeding, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against bacterial seeding outside of a research setting until we know more about its safety and benefits.

The first three years: a time of flux

A child's immune system is biased against inflammation during their first three years, priming the body for bacterial colonisation.

When a child eats a new food or digs into the earth and touches their mouth, they collect a kaleidoscopic sample of microbes. Many will perish, but some will survive the perilous journey to the colon.

In these formative years, the microbiome population is in constant flux; factions rise and fall; species come and go, whilst some founding fathers successfully settle, building robust settlements in the gut.

Children source microbes from a dizzying array of places, though some factors play a greater role in shaping the infant microbiome than others, as we shall explore now;

Breastfeeding: fertiliser for the microbiome

Once upon a time, breast milk was thought to be sterile, but this couldn't be further from the truth.

Breast milk is a creamy bacterial soup with both prebiotic and probiotic properties.

Oligosaccharides promote the growth of beneficial bacteria such as bifidobacterium, acting as microbiome fertiliser.

By promoting "good" gut bugs, breast milk aids in the development of the infant's immune system, which may explain why it's associated with a reduced risk for asthma.

Better still, breast milk confers the child with some of mums immunity, protecting against potentially pathogenic bacteria- It really is a super supplement for newborns!

Besides the birthing method, breastfeeding is the most important determinant of infant bacterial composition.

In light of this, it may not surprise you to learn that breastfeeding appears to mitigate disruptions to the microbiome after a c-section birth, potentially reducing a person's risk of complications later in life.

Puppy power: pets and microbiome diversity

As children explore and interact with the world, they collect an array of bacteria; every time a child licks a window, gnaws on their parent's finger or kisses the family pet, hordes of bacteria gain entry into the promised land of the body.

Speaking of pets, our furry companions can exert a significant influence over the developing microbiome.

For example, a study published in Microorganisms found that children living alongside dogs had a distinct microbiome composition compared to those without canine companions.

In particular, the pet-owning children had a higher abundance of Bacteroides and short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria.

When the dogs were given a canine probiotic, shifting their microbiome composition, the children also exhibited changes in their microbiome diversity.

According to another study, early life exposure to animals can increase the abundance of two types of bacteria, namely Ruminococcus and Oscillospira, both of which are associated with reduced risk for childhood atopy and obesity.

Last but not least, children in rural communities often possess higher microbial diversity than their urban counterparts, which researchers partly attribute to contact with domestic and agricultural animals.

Rubbing off on each other

Children pick up habits and behaviours from family and friends as they develop, but that may not be all they inherit from those closest to them.

In one study, children attending the same daycare centres showed increasing similarities in their microbiome composition.

What's more, daycare children possessed unique microbial profiles compared to homeschooled children, boasting higher diversity levels.

The microbiome stabilises at around three years old, at which point it becomes more resilient to change, though not completely static. The microbiome also undergoes major vicissitudes during adolescence and pregnancy.

How to nurture a growing microbiome

Now you know how humans acquire their microbiome, including its impact on health, you might be wondering how you can best nurture a growing microbiome in children. Below, we've compiled some practical, evidence-based ways to cultivate diversity in little ones.

-

1.) Breastfeed instead of bottle-feeding (where possible).

-

2.) Feed the child a prebiotic baby formula if breastfeeding is not an option.

-

3.) Socialise the child with family/friends to diversify their microbial population.

-

4.) Once the child graduates to solid foods, ensure they eat plenty of fibre, though introduce this slowly to avoid digestive upsets.

-

5.) Allow them to play out and interact with soil, but practice good hygiene and ensure the child washes their hands before eating and after touching animals.

-

6.) Use antibiotics judiciously (for example, antibiotics are often prescribed for viral infections, despite being incapable of treating such conditions).

If you were formula fed or born via caesarian section, you needn't worry. The extent to which the first three years shape later health is up for debate, and even if this developmental window does have downstream effects, the microbiome remains dynamic into adulthood.

As such, you can cultivate a healthy microbiome through your lifestyle and dietary choices. Moreover, it is far more productive to focus on what you can change in the present than dwelling on factors out of your control.

Want to be proactive about your gut health? When you take the Atlas Microbiome Test, you'll discover which bacteria you have, which you lack and how to cultivate the ones you need. We'll also send you weekly, personalised food recommendations to boost beneficial bacteria in your gut.

Key takeaways

To summarise, a child first encounters bacteria during birth, either through the vaginal canal or contact with the skin during a caesarean section.

It's first community of microbes is largely maternal, but may also include some of dads microbes or those lingering in the hospital.

Research suggests that how we are born shapes our initial microbiome composition; for example, those born via caesarian section possess a microbiome enriched in maternal skin bacteria and resilient microbes from the hospital environment.

On the contrary, children born via the vaginal canal have higher levels of key microbial communities like lactobacillus, although these differences fade after a year.

The extent to which this affects health later is not entirely clear, though research has associated c-section delivery with an increased risk for asthma and food allergies.

It is hypothesised that disruptions to the microbiome during the "developmental window" of the first year may hinder our immune education, overseen by the gut microbiome.

Besides the delivery method during birth, breastfeeding is a major determinant of early microbiome composition, with possible downstream effects.

For example, children reared on breast milk show greater diversity than formula-fed babies and have lower rates of asthma and obesity in later life.

Children living alongside animals also display greater diversity than those without pets or livestock, partly explaining why children in rural areas often possess greater alpha diversity than their urban counterparts.

The infant microbiome is inherently unstable for around three years, undergoing dramatic and constant flux. After this period, the environment stabilises, and the microbiome becomes more robust to changes.

Nonetheless, the microbiome remains dynamic in adulthood, meaning our dietary and lifestyle choices continue to shape it's composition.

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.