The microbiome exists symbiotically with us, shaping immunity, metabolism, digestive health and potentially even mood. But what constitutes a "healthy" microbiome, and how can we cultivate our gut bugs to improve well-being? Join us as we explore this question.

Table of contents

- The gut microbiome: your inner jungle

- Diversity and balance: key markers of microbiome health

- Butyrate-producing bacteria and anti-inflammatory potential

- The good, the bad and the commensal

- What constitutes an unhealthy microbiome?

- Challenges in the hunt for a healthy microbiome

- How can I improve my overall microbiome health?

- Key points to remember

The gut microbiome: your inner jungle

The microbiome is a dynamic ecosystem populated by trillions of microbes competing for space and nutrients.

Think of the gut like a rainforest, but instead of monkeys, insects and birds, it's teeming with communities of archaea, protozoa, eukaryotes and most abundant of all, bacteria.

Once upon a time, researchers thought the gut bacteria were harmless hitchhikers, neither beneficial nor detrimental to health.

In the last two decades, the microbiome has been shown to play a key role in human health, influencing immunity, metabolism and potentially even mood.

We now know that the microbiome exists symbiotically with us; they need us for a place to live, and we rely on them to perform numerous complementary functions.

It might surprise you to learn that bacterial genes dwarf our human genome, numbering 20 million compared to our 20,000 human ones!

Depending on the birthing method, we acquire our first smattering of bacteria at birth, either from our mother's birth canal or her skin.

Interestingly, early disruptions to the microbiome due to caesarian section or bottle feeding are associated with health defects downstream, including allergies and autoimmune disorders.

Furthermore, imbalances within the microbiome are widely observed in those with conditions like depression, autism, obesity and colon cancer, hinting at a bacterial component to these diseases.

In light of these connections, it's only natural to wonder what constitutes a healthy microbiome, but whilst the question is relatively simple, the answer is surprisingly complex and presents numerous challenges.

One thing is clear: no single "healthy" microbiome composition exists. A healthy jungle ecosystem is vastly different from a healthy arctic ecosystem, though both are stable and allow resident species to thrive. Likewise, a "healthy" microbiome can come in multiple shapes and sizes.

Diversity and balance: key markers of microbiome health

The microbiome is more or less stable during adulthood, though not entirely immutable. Multiple factors impact microbiome diversity, including diet, lifestyle, antibiotics, and geography.

Researchers widely agree that diversity and balance are broad stroke markers of microbiome health.

In short, both of these parameters increase the stability of the gut ecosystem, allowing it to "bounce back" from disruptions, including antibiotics or stress.

Picture the microbiome as a verdant forest; a woodland ecosystem characterised by biological diversity is better equipped to recover from ecological stress, such as a forest fire or deforestation.

Likewise, a woodland where species are equally distributed prevents any single organism from taking over, such as weeds or pests.

In much the same way, diversity and balance in the microbiome make the overall ecosystem more resilient to disturbances, protecting it against a pathogenic takeover.

A diverse microbiome also possesses a more varied skill range, as more microbes mean more specialisation. You wouldn't want a football team made up of eleven defenders, nor should you want a microbiome specialised in one skill alone.

Butyrate-producing bacteria and anti-inflammatory potential

When certain bacteria ferment indigestible fibre, they belch out short-chain fatty acids as a by-product, including:

- butyrate

- acetate

- propionate

As such, an enrichment in butyrate-producing bacteria is considered an indicator of microbiome health, offering protection against inflammatory diseases.

The main butyrate producing-bacteria in the human gut belong to the phylum Firmicutes, in particular, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Clostridium leptum of the family Ruminococcaceae, and Eubacterium rectale and Roseburia spp. of the family Lachnospiraceae

☝DID YOU KNOW?☝When you take the Atlas Microbiome Test, we measure the inflammatory potential of your microbiome by calculating the amount of butyrate-producing bacteria in your gut.

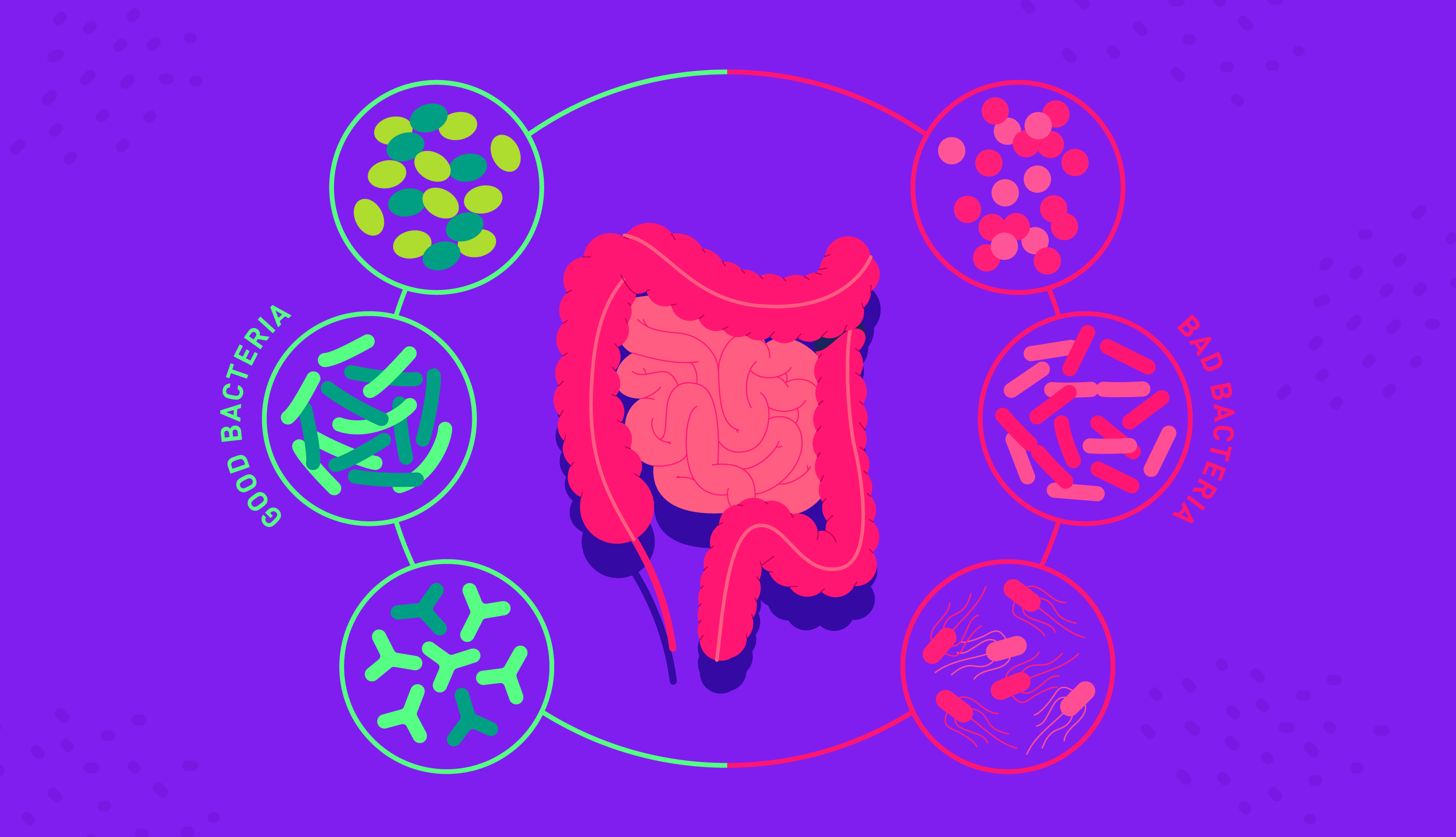

The good, the bad and the commensal

We can very broadly categorise bacteria into three types: beneficial (probiotic), harmful (pathogenic), and commensal bacteria.

Commensal bacteria are microbes that are either harmless or potentially beneficial to health. These bacteria are useful as they take up space that pathogenic bacteria could otherwise occupy.

With that said, it is perfectly normal for a microbiome to contain pathogenic species such as E-coli and Enterococci, and considering these species "bad" is an oversimplifiction.

☝TIP☝When you take the Atlas Microbiome Test, you'll discover the proportion of beneficial and commensal bacteria in your gut.

What constitutes an unhealthy microbiome?

One way to understand what constitutes a healthy microbiome is to observe gut bacterial composition in those with certain diseases. By doing so, researchers can look for patterns which might indicate potential microbial risk factors.

Researchers use the same method to identify genetic predispositions to illness; however, the dataset for the human genome is far more extensive at present.

For comparison, there are upwards of 20 million sequenced human genomes publicly available, compared to around 400,000 microbiome samples.

Nonetheless, there are already early indications for what might constitute an "unhealthy" or "pathological" microbiome composition.

Generally speaking, dysbiosis is defined by reduced species diversity and enrichment in pro-inflammatory bacteria.

It remains unclear whether dysbiosis is a cause, consequence (or both) of these disease states.

☝TIP☝With the Atlas Microbiome Test, you'll discover your risk level for five non-communicable diseases, including ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and obesity. To calculate this, we compare your sample against the microbiome profiles of those with these diseases; the higher the similarities, the greater your risk factor score will be.

Challenges in the hunt for a healthy microbiome

While researchers have identified several broad markers of microbiome health, there are still massive gaps in our knowledge which preclude a more detailed definition.

Firstly, the microbiome samples we have are few and biased, with the majority of data sourced from highly developed countries.

In industrialised societies, caesarian section births, hyper cleanliness and increased antibiotic use are commonplace- all factors known to disrupt microbiome diversity.

Whilst an individual from an industrialised society may be disease-free, this doesn't necessarily mean that their microbiome composition is "ideal" or "normal".

Emerging research suggests that beneficial species are becoming extinct in developing countries owing to increased industrialisation.

For example, certain bacteria can degrade cholesterol in a unique way, expelling it through faeces as coprostanol and preventing it from cycling through the liver, gut and bloodstream.

Interestingly. Poyet et al. found that the levels of coprostanol secreted in the faeces increase according to the subjects' industrialisation level.

Moreover, the microbe suspected of degrading cholesterol, called Eubacterium coprostanoligenes, is most commonly found among populations living in less industrialised ways, indicating that our modern way of life is culling probiotic species.

The bias towards European microbiome samples in public databases may be hiding even more beneficial microbes rendered extinct by industrialisation.

At present, there is a dearth of data on the microbiome composition of whole regions, including South America, South East Asia and Africa. One can only guess what microbial surprises are in store.

Despite being robust, diverse and balanced, the Hadza microbiome is noticeably depleted in the probiotic bifidobacterium, with seemingly no adverse health effects.

Besides being a powerful reminder that microbiome health comes in many different shapes and sizes, it also highlights the gaping holes in our knowledge at present.

Without more representative microbiome samples, it is difficult to determine what a "normal" or "healthy" microbiome composition looks like beyond broad markers.

Moreover, many studies that have established an association between microbiome composition and diseases only capture a snapshot of the microbiome at one point.

If microbiome perturbations precede illness, these studies can fail to identify the microbial red flag.

Additionally, whilst the microbiome has been directly associated with numerous intestinal and extra-intestinal diseases in mice models, few studies have demonstrated causation in humans.

How can I improve my overall microbiome health?

Your gut bacteria eat what you eat, which is why diet can shape the communities of bacteria living in the microbiome. In order to encourage probiotics in your gut, you have to ensure you are eating the types of food they thrive on, which happens to be prebiotic plant-based fibre.

No amount of probiotics can compensate for a diet lacking in gut-loving fibre or nutrients simply because they won't have anything to sustain them if they make it to the intestines.

Eating a diet rich in indigestible fibres like inulin can encourage probiotic bacteria in your gut and cultivate diversity. A few examples of foods known to be powerful prebiotics are:

- chicory root

- Jerusalem artichoke

- onions

- garlic

The Mediterranean diet, rich in prebiotic legumes, nuts, seeds, fruit and vegetables, has been shown to increase overall diversity and probiotic bacteria in the microbiome.

With the Atlas Microbiome Test, you'll receive weekly tailored nutritional recommendations to help you improve your gut health. Better still, you can log your meals with our award-winning photo tracking technology, receiving a gut-health score for each dish!

☝TIP☝Try upping your fibre consumption gradually to avoid digestive upsets like bloating and gas.

Key points to remember

- Researchers widely agree that diversity and balance are broad markers of microbiome health, increasing the resilience of the gut ecosystem against pathogenic takeover and disruptions such as antibiotics.

- Researchers broadly categorise bacteria into probiotic (beneficial), pathogenic (harmful) and commensal (harmless) species. The abundance of probiotic and commensal bacteria is used as a general parameter of microbiome health; the higher the levels of each, the better.

- Dysbiosis is characterised by reduced diversity parallel to an increase in pro-inflammatory species. A dysbiotic microbiome profile is present in numerous intestinal and extra-intestinal disorders, including depression, autism, irritable bowel disease, colon cancer and obesity.

- It is unclear whether dysbiosis is a cause, consequence (or both) of these disease states, though we can confidently say it's no marker of health.

- There are large gaps in our knowledge about what constitutes a healthy microbiome, precluding a more specific definition.

- Eating a diet rich in prebiotic fibre can boost beneficial bacteria and cultivate diversity in the microbiome. In particular, the Mediterranean is associated with increased microbiome diversity and a reduced risk for obesity, heart disease and all-cause mortality.

☝️DISCLAIMER☝This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to constitute or be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.