Butyrate is produced by your gut bacteria and supports digestive health and disease prevention. It's real, it’s measurable, but what on earth is it?

Butyrate is one of the reasons why the relationship between our species and the microbiome has been described as “symbiotic”: our shared existence is beneficial to both parties involved. In this case, our gut bacteria digest tough plant fibres for us and turn them into a number of organic compounds, including “short-chain fatty acids” (SCFAs) that have scientifically-proven benefits for our health and well-being.

Case-in-point, butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid that provides fuel for the cells of our gut lining, supports immune system functions of the colon wall and protects against certain diseases of the digestive tract. There are other SCFAs like acetate and propionate, but the benefits of butyrate are particularly well-researched.

What is butyrate and how is it made?

Interest in the microbiome is growing daily, and yet, accessible and reliable information about its functions can be hard to come by, as is the case for butyrate. This journey of discovery starts with a basic introduction to the microbiome, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs, remember?) and, finally butyrate.

In particular, one of these functions is to break down dietary fibre that has travelled through the digestive tract, because the human body can’t. This process, known as fermentation, yields a variety of metabolites including butyrate, an organic compound that belongs to the group of “short-chain fatty acids”. These health-promoting molecules are an important energy source for the body, providing anywhere from 5% to 15% of a person’s daily caloric needs.

Butyrate is the main fuel for the cells that line the gut, known as “colonocytes”, providing up to 90% of their energetic requirements. In other words, butyrate helps these cells fulfil their functions correctly, thus maintaining the integrity of the gut lining, called “mucosa”. In fact, “several studies have linked impaired butyrate metabolism with mucosal damage and inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases including ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease”.

Butyrate is starting to sound important now, right?

How does butyrate improve our health?

This SCFA has a number of benefits at many levels, ranging from macroscopic (that you can visibly identify) to genetic where it helps regulate the function of a number of genes involved in inflammation and immune response.

As previously mentioned, butyrate serves as a primary source of fuel for colonocytes, the cells that line the gut. As demonstrated on mice, these cells, if deprived of energy, start to degrade (a process known as “autophagy”), but can be rescued by increased consumption of butyrate.

This short-chain fatty acid has an antioxidant function that helps maintain a healthy gut. It promotes the growth of villi, microscopic finger-like extrusions that line the intestines, and enhances the production of mucin, a gel-like substance that coats the inside of the gut. These mechanisms explain how it helps maintain the integrity of the bowel wall, known as the "epithelial defence barrier", that prevents bacteria, toxins and other substances from crossing into the bloodstream from this organ.

It has been shown to help the colon (large intestine) absorb electrolytes that are essential for many physiological processes and may be beneficial in the prevention of certain types of diarrhoea. Butyrate also regulates colonic motility, natural movements of the gut that move food through it, and increases blood flow in the colon.

How can I enhance my microbiome’s butyrate production?

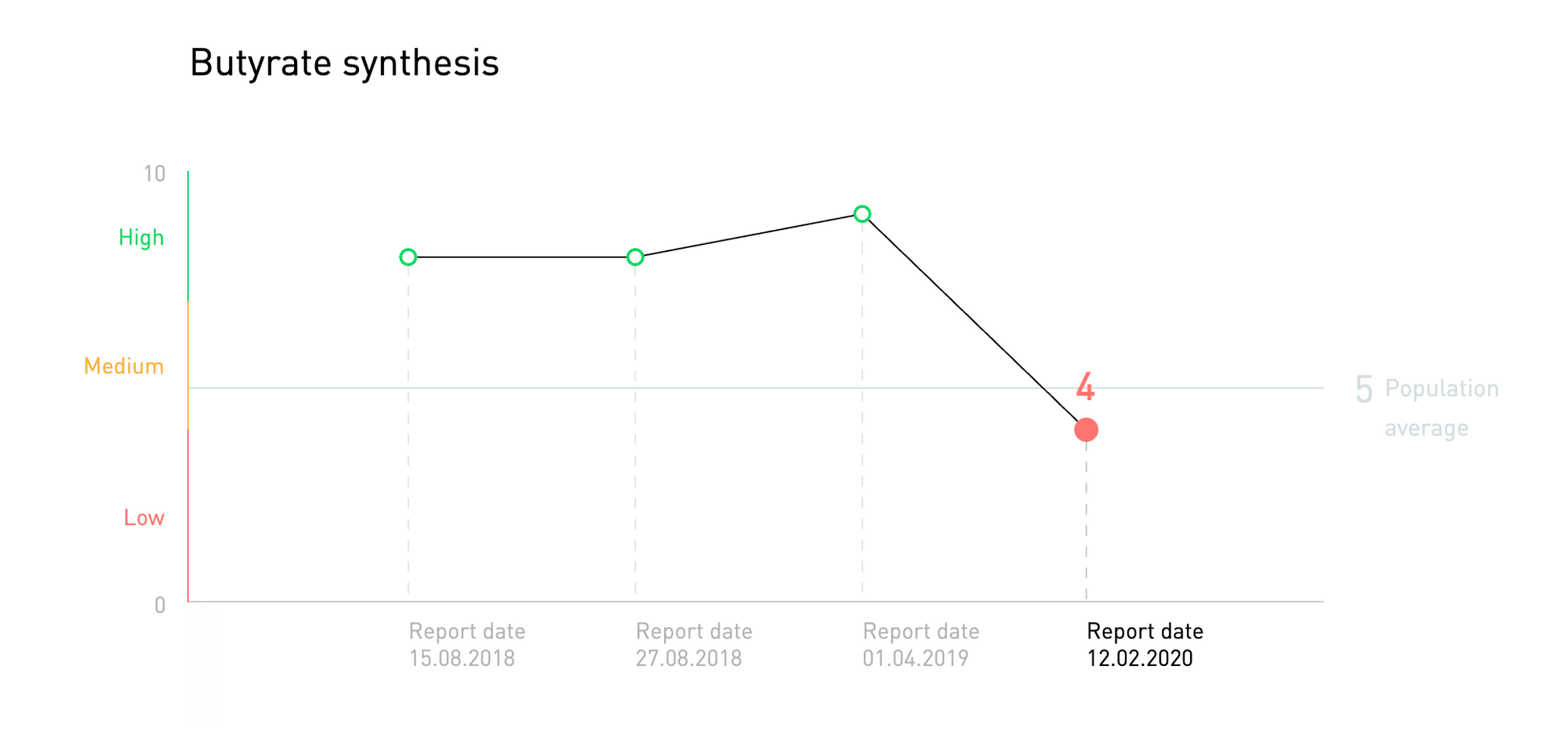

Members of the Firmicutes phylum, a classification of bacteria, are particularly known for their butyrate-producing capacities. Those who have had their microbiome tested with Atlas can consult the butyrate tab in their personal account, takers of other microbiome tests could consult the list of bacteria present for Anaerostipes, Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, Eubacterium and Gemminger.

Consuming foods that are “prebiotics” (food that nourishes the microbiome directly) through diet has been shown to optimise butyrate production. Prebiotics are foods, mainly vegetables, pulses, fruit and whole grains, that are not only delicious for the human palate, but also popular with your gut bacteria. They contain dietary fibre that passes through the body undigested to feed the microbiome living in your colon.

There are a lot of suggestions online how to increase butyrate in the gut like consuming more butter or taking butyrate supplements. However, eating butyrate won’t necessarily benefit your gut rarely because if you ingest butyrate, it can be absorbed by the stomach, meaning it won’t reach the large intestine to fuel its cells.

It’s also worth noting that high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate diets have also been shown to disrupt butyrate production in the microbiome. In one study, researchers analysed the microbiome of obese participants who went on a short-term diet that limited their carbohydrate intake, thus limiting their consumption of plant-based dietary fibre.

After 4 weeks of consuming a low-carbohydrate diet (24g per day) and another 28 days on a moderate-carbohydrate diet (164g per day), the concentration of SCFAs was lower than on a high carbohydrate diet (399g per day). It was specifically demonstrated that butyrate concentrations decreased when carbohydrate intake was reduced. The same study also found a link between the density of Firmicutes bacterial species, Roseburia and E. Rectale, and butyrate concentrations, both of which decreased as carbohydrate intake was reduced.

In short, swapping out complex carbohydrates and whole plant foods for a diet dominated by animal protein and fats can have a negative impact on your bacteria’s ability to fulfill their destiny in your journey to health and well-being. Vegetables are your friends, readers. Fruit and whole grains too. Not to mention fermented foods, just not right now in this butyrate scenario.

The best way to optimise butyrate production is to adopt a high-fibre diet that will encourage butyrate-producing bacteria of the microbiome in your colon. Nevertheless, every person’s microbiome is unique, and each bacterium has its own preferred source of prebiotics.

This is why the Atlas Microbiome Test analyses the ratio of butyrate-producing bacteria and evaluates the microbiome’s overall butyrate production capacity. This data is then used to create a personalised list of recommended foods that will encourage the existence of beneficial microbial species in the gut for digestive health, disease prevention and overall well-being.

☝️ Remember

1. Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid produced by the microbiome.

2. Made by bacterial fermentation of undigested dietary fibre.

3. Helps prevent inflammation of the gut.

4. Contributes in preventing colorectal cancer.

5. Supports villi growth and mucin production.

6. Negatively affected by high-protein, high-fat, low-carb diets.

7. Mainly produced by Firmicutes bacteria.

8. Important source of fuel for cells of the gut lining.

9. The Atlas Microbiome Test evaluates butyrate production by the microbiome

- Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 35, 8–15. Levy, M., Blacher, E., & Elinav, E. (2017).

- Implications of butyrate and its derivatives for gut health and animal production.Andrea Bedford, Joshua Gong, Guelph Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (2017).

- From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell, 165(6), 1332–1345.Koh, A., De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., & Bäckhed, F. (2016).* Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 35, 8–15. Levy, M., Blacher, E., & Elinav, E. (2017).

- Colonic mucin synthesis is increased by sodium butyrate. Gut. 1995 Jan;36(1):93-9.Finnie IA, Dwarakanath AD, Taylor BA, Rhodes JM (1995).

- Butyrate and the colonocyte. Production,

absorption, metabolism, and therapeutic implications. Adv Exp Med Biol.

1997;427:123-34.Velázquez OC, Lederer HM, Rombeau JL. - Reduced Dietary Intake of Carbohydrates by Obese Subjects Results in Decreased Concentrations of Butyrate and Butyrate-Producing Bacteria in Feces. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 73(4), 1073–1078. Duncan, S. H., Belenguer, A., Holtrop, G., Johnstone, A. M., Flint, H. J., & Lobley, G. E. (2006).